Lately, an unusual garden has been growing at the Fundació Joan Miró – a garden designed by the artist Pep Vidal for bees and other insect pollinators, providing them with a pace of their own, without boundaries or conditions. Inspired by this project, Vicky Benítez, a Fine Arts graduate and professional gardener, offers us a nostalgic look at a lost, denatured world, dominated by the artifice of gardens that are organized according to primarily aesthetic criteria. Vicky Benítez proposes that we tend our gardens with a full awareness that we are not tending the body, but rather the soul; and she stresses the importance of urban vegetable gardens as spaces for social cohesion where nature (both human and non-human) can grow and develop freely.

This article and the Mil flors (A Thousand Flowers) installation by Pep Vidal are part of the Beehave project, which will be held at the Fundació and at several other locations throughout Barcelona beginning in February 2018.

Gardens Don’t Exist; They’re An Illusion

I studied gardening at the Institut Rubió i Tudurí in 2001 and have been working in this field ever since then. One of the things I have learned from gardening is that I don’t know anything. That everything I hold to be true is questionable.

I admire people who speak with passion, but I prefer those who doubt – the ones who understand that, in the multiple layers that make up our knowledge, what we don’t know makes it impossible for us to understand how life really works.

Poem by Walt Whitman. Moss on paper

Gardens attempt to tame nature, which isn’t possible; therefore, gardens can’t exist. It’s impossible insofar as we make a huge effort to impose order in a system whose deepest inner workings we don’t understand. If we view plants as inanimate beings, we are making a mistake: they are beings with feelings, communicating and reacting on levels that we are just beginning to discover today, as Stefano Mancuso shows us in this video. For years – for centuries – we have been researching, observing, classifying, categorizing plants and now we are starting to realize that our belief system is wrong.

In cities, we choose plant species for their size, their colour, their flowers or their capacity to produce allergens that affect people, and we are under the false impression that the trees we choose are going to remain as we expect, squeezed into a one-cubic-metre planting hole to grow (with any luck) surrounded by concrete. In addition, we ask them not to make a mess with their leaves, fruits or flowers. Since they refuse to do as they’re told, we mutilate them. Since they get sick from their wounds after the mutilations we’ve inflicted upon them, we treat them with chemicals. Since we also object to the grass that sprouts in their pits, we poison the soil with glyphosate.

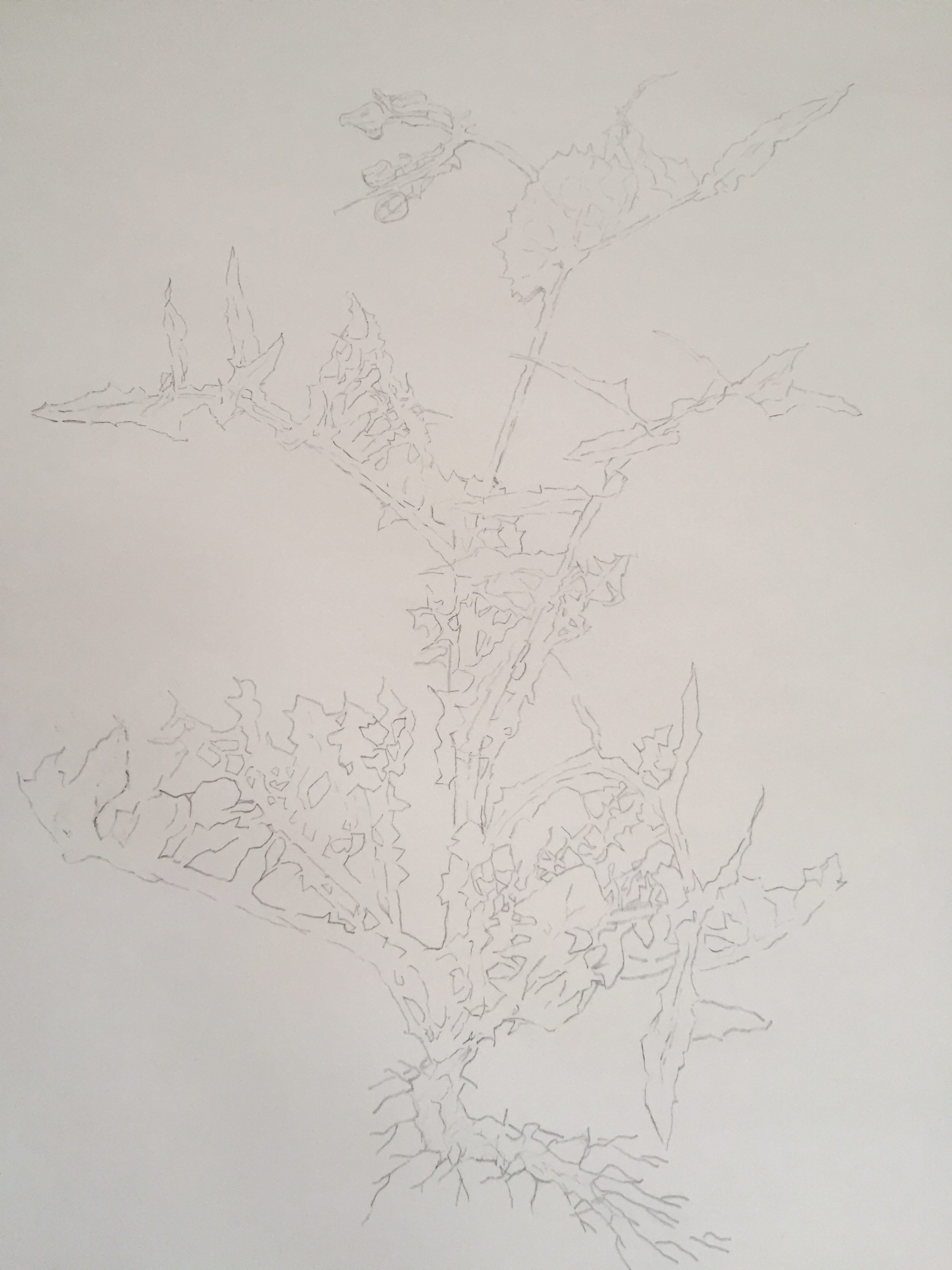

Weeds drawing

We have done away with autumn, and I’m not just referring to climate change, but also to human stubbornness for wanting to organize and clean up what is only natural. Not that long ago, when we were coming back from school with a carpet of leaves on the ground, we knew autumn was on its way. We jumped on them, picked them up and used them to make murals at school. There are no more carpets of leaves: someone decided they were dirt, and the rest of us accepted it is as a fact; we prune trees so that they won’t drop their dirty leaves on our clean streets. Autumn has disappeared.

Some gardens are like Ikea paintings: mass produced, with contained, austere designs. All the same. They’re like that because the standard formula is applied, the list: Mediterranean plants that are local so they won’t need much water; the occasional tree that won’t be too messy; cement, and pieces of street furniture with impossible designs so that nobody will settle into them for too long, so that no one will socialize, lest public spaces should actually turn out to be useful and public. Gardens that bring on a disturbing sense of déjà vu. A non-place.

Square in Selva del Camp, Tarragona

When did we lose our connection with nature? When did we cease to view ourselves as a part of it? Maybe we had that connection sometime ago, maybe the best choice is to recover it, to consider every living creature as an individual with specific needs, instead of applying received ideas, instead of applying lists. We have tended to simplify knowledge, to apply it in lists of elements that lack an overall perspective of the environment’s specific circumstances. All our knowledge is based on what we have been told, on what we have experienced, on what we have been taught must be a certain way. Down deep, we all know that what is could be different – in other words, our perception, our knowledge and our experience are the product of multiple circumstances and just by changing one of the variables the result would be different. If only we were capable of destroying our belief system, of atomizing it until not even the smallest particles were left. Of seeing life with new eyes. We are irrelevant over time; plants show us it’s so. When we have disappeared, they will live on.

There are gardens – those which some malicious landscape architects label as kitsch – that are excessive, don’t follow lists, where we find those cursed plants that are qualified as exotic or invasive; gardens that spread out, overflow. They seek the usefulness of being disorganized, natural, chaotic spaces. They understand that gardens don’t exist, that they’re an illusion, and that they feed on that illusion in order to be.

An example is Antonio’s Bona Estrella (“Lucky Star”) garden in Bonastre – a secret, inaccessible garden, tucked away among the hills; a garden for contemplation, not for the pleasure of beauty, but of thought. A cacti collection of sorts that Antonio began fifteen years ago and to which he devotes between eleven and sixteen hours a day. For this man, gardening is a way of being in the present, of focusing his thoughts, of flowing in time. He is the archetype of what we consider a gardener from a romantic point of view, a wise man (remains of heteropatriarchy, which keeps on popping up in our collective imagination) after so much time spent alone, meditating. Antonio carries out an astonishing, unreal construction, covering a huge area of over three hectares, devoting thousands of hours to a colossal endeavour. Antonio is the exception. The acceleration of time and the production system have reached gardening to ruin the myth. And yes, also to abolish the idea of a genre linked to work. This garden is only possible because it has been created outside a paid work system.

Bona Estrella garden, Bonastre

Some urban gardens are useful, not only to provide food for its members, but also to contribute towards social cohesion within cities that are becoming increasingly anonymous and individualistic, offering venues where public space is interwoven with nature. They are places that fight off gentrification, that stem from the willingness to improve the neighbourhood; spaces for opening up, both through cooperative work and through a dialogue in search of the common good.

La Vanguardia garden, Poblenou

There is a garden in the making – or rather in the growing – that Pep Vidal designed for bees, in which they will decide to feed on the pollen of the thousand plants (one thousand different taxons) that will flower there, wherever and whenever they please. A place that shows how the gardener proposes and nature disposes. I like the idea of grasses growing and nobody qualifying them as weeds. How can a plant be judged to be a weed?

It’s lovely to think about a garden made to feed bees in a city whose regulations don’t allow urban beekeeping – a garden made with the hopefulness of someone who knows that nature refuses to be controlled. Bees will live in Barcelona or wherever they please. How arrogant to think otherwise!

Mil flors (A Thousand Flowers) project by Pep Vidal at the Fundació Joan Miró