On the occasion of the exhibition The Way Things Do, which celebrates the 30th anniversary of Fischli and Weiss’s iconic filmThe Way Things Go at the Fundació Joan Miró, Ivan Pintor looks at the way the Swiss duo’s film and the works by the young artists taking part in the exhibition connect with the comic strip and cinema tradition.

Ivan Pintor holds a PhD in Audiovisual Communication from Pompeu Fabra University and specialises in comparative cinema, audiovisual narrative and the history of the comic strip. In his article, Pintor investigates how chain reactions, constant motion and technological complexity have been addressed from Rube Goldberg’s cartoons and the weekly comic TBO to slapstick and science fiction films.

The Way We Are Made

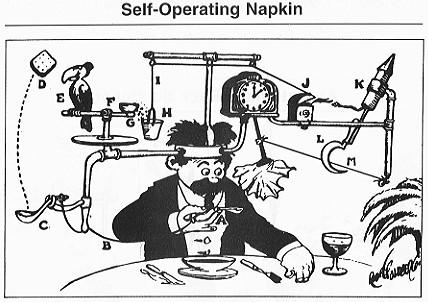

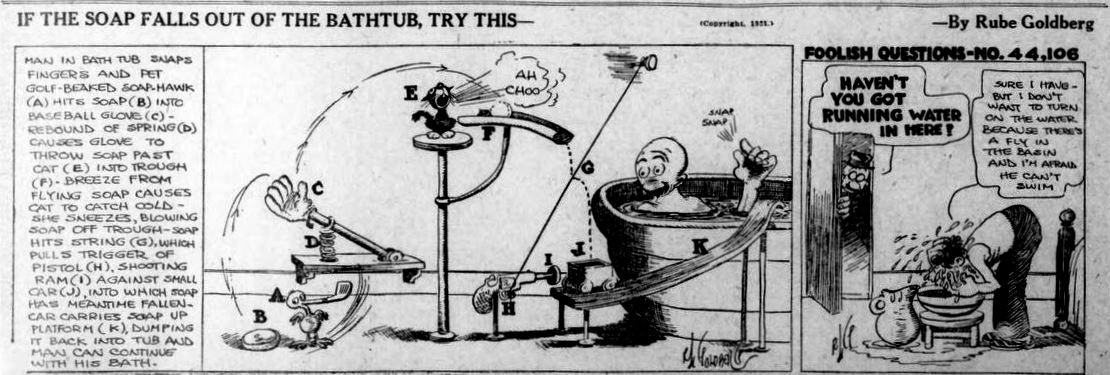

The somewhat derogatory Spanish expression “son inventos del TBO” (“these are comic strip inventions”) originates from the outlandish machines cartoonists like Nit, Benejam and Francesc Tur y Sabatés created for the Spanish comic TBO. The machines used the mechanism of a chain reaction to create complex pieces of engineering that were used to perform humdrum tasks. They were attributed to a fictional character, Professor Franz of Copenhagen. The over-elaborate chain effect of a set of absurd cogs and interconnecting parts was, to some extent, a reaction against the bureaucratic logic of the Franco regime and, at the same time, the growing technological saturation of the modern world, and recreated the elaborate machines devised by the American cartoonist Rube Goldberg in the series The Inventions of Professor Lucifer Gorgonzola Butts (1914-1964).

The expression “Rube Goldberg machines” has been absorbed into colloquial English, in the same way as “inventos del TBO” has into Spanish. They have the double meaning of describing a pointless endeavour or an outlandish machine that is efficient but, ultimately, idle and inoperative. It is in this final inoperability that Rube Goldberg, as Charlie Chaplin did later in Modern Times (1936), exposes the fragility of humanity when faced with a technology whose sole purpose is to achieve constant, hypertrophied growth. The ability of gags and slapstick to capture the continuity between the forms of slavery of classical antiquity and contemporary technology has endured through the work of filmmakers such as Jacques Tati to contemporary cinema, which has been compelled to reformulate the physical and contingent idea of technology as software that often takes over an individual’s willpower — from Paul Verhoeven’s Total Recall (1990), and the Wachowski sisters’ Matrix (1999) to Spike Jonze’s Her (2013).

Rube Goldberg, Self-Operating Napkin, 1931. Creative Commons

Rube Goldberg, If the Soap Falls Out of the Bathtub, Try This, 1921. Creative Commons

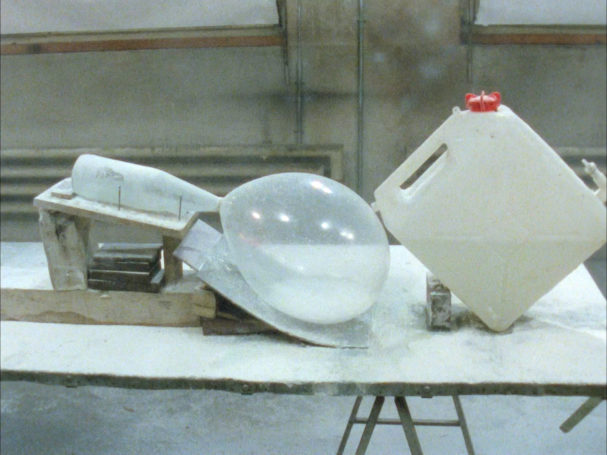

When the Swiss artists Peter Fischli and David Weiss presented their film Der Lauf der Dinge (The Way Things Go) at Documenta 8 in Kassel (Germany) in 1987, the idea of a software that was capable of colonising reality had not burst onto the scene, and inoperability, movement, transitivity and a chain reaction appeared in their most specific guise, exactly as they had done in Rube Goldberg’s cartoons and in Los inventos del profesor Franz de Copenhague (The Inventions of Professor Franz of Copenhagen), in the comic TBO. The arts scene of the 1980s was largely defined by paintings as objects with economic benefits and Fischli and Weiss drew people’s attention to process, the mobility of which also connected with the comic strip tradition and the break that cinema had made in previous decades.

At the exhibition The Way Things Do, curated by Martina Millà and Serafín Álvarez for the Fundació Miró to commemorate the 30th anniversary of The Way Things Go, Daniel Jacoby and Yu Araki’s video installation Mountain Plain Mountain is one of the works by young artists that reread the influence of Fischli and Weiss’s film. It traces the endless movement, the ecstasy and everyday banality of Japanese horse races, ban’ei, at the only stadium where they are still held, in Obihiro. The sequence of images showing bets being placed, the results, photo finishes and cash registers paraphrase the shots of money changing hands in Bresson’s film L’Argent (Money, 1983), or the beautiful sequence in another of Bresson’s films, Le Diable, probablement (The Devil, Probably, 1977), which shows, in a pared-down, elliptical montage, the tiniest movements of the passengers on a bus, social causation, the constant interaction between efficient cause and chance.

Mountain Plain Mountain. Daniel Jacoby & Yu Araki, 2017

Mountain Plain Mountain not only highlights how The Way Things Go drew attention to process through film, but also the close connection of the film to Bresson, Dreyer and Ozu’s so-called “transcendental cinema”. The povera gesture of choosing bin bags, discarded bottles, old unused boards, water, alcohol, oil, soaps and left-over solvents – the remains of industrial praxis in an old warehouse – to build the work is also accompanied by a rigorous, ascetic mechanism based on the attitude of a camera that must, at every moment, foretell the following concatenation: a bin bag pushing a wheel, which makes a plank tip over and a step ladder slide down a board and knock against a table which flips over a mattress that in turn triggers the downward trajectory of a ball that ends up overturning a bottle of acid, in a domino effect further exacerbated when, for the first time, fire appears: the most intense gesture of pathos and transmission throughout the work.

It is no coincidence that a painter, visual artist and filmmaker like David Lynch was immersed, during the same period, in his fish kits, which show you how to reassemble the parts of recently cut-up fish based on the idea of self-assembly modular furniture, or in a TV series like Twin Peaks (1989), where the chain of events, the law of transmission and fire play a central role. The slogan of the TV series, “Fire walk with me”, could also be the slogan for The Way Things Go from the moment the flames appear. The metaphysical backdrop, the centrality of what is known in Zen as permanent impermanence, and the idea that the only thing that neither begins nor ends is the being itself, appears, in the hands of Fischli and Weiss, in a humorous guise. How to place emotions on things? How to achieve a stripped-back effect and literal meaning through dramatic composition? How can the unproductive and its inoperability drive a wedge between the imperative of consumption and the productivity of capitalism?

The Way Things Go is, of course, a film designed to be screened in an exhibition space. The same is true for the previously mentioned video installation Mountain Plain Mountain and the installation One Step Closer to the Finest Starry Sky There Is, a vast assemblage of merchandise associated with sci-fi stories, created by the exhibition curator Serafín Álvarez. Nevertheless, and as Álvarez’s work underlines, the visual and narrative driver of Fischli and Weiss’s film is highly cinematographic: a trigger for an action that is not far removed from that of contemporary neo-Hollywood, from George Lucas’s Star Wars (1977) to Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). It is, certainly, this cinematic nature that has transformed this film into a space for fertile contact between the visual arts and popular entertainment, as almost identical sequences are repeated in films as different as Back to the Future III (1990), The Goonies (1985), Delicatessen (1991), Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure (1995), Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit (2005), Robots (2005) and Toy Story (1995), and even entertainments such as Human-Powered Freerunning Machine (2012), by parkour performer Jason Paul.

One Step Closer to the Finest Starry Sky There Is. Serafín Álvarez, 2017

Leaks. Cécile B. Evans, 2017

Cécile B. Evans’s installation Leaks (2017) features five monitors screening a rereading of The Way Things Go as a work of science fiction, while it conjures up the idea of technological speculation and the permanent possibility of catastrophe. The troubling presence of robots watching screens in the films shown on the five monitors not only confronts the viewer with their own post-human avatars, but also reveals a glimpse of a disaster by including images of an air crash. Evans rereads the horizon of the catastrophe through a series of static panels in her previous work, Sprung a Leak (2016), a play that, like the avant-garde dramas imagined by Maurice Maeterlinck, seeks out the static nature of non-human figures, connected, in this case, by a closed circuit. On one of these panels, a robot stands among the wreckage of a disaster – like a futuristic Raft of the Medusa – and, through a strip of text, seems to act as the spokesperson for the subjectivity of specific objects, excluded from the consumer cycle and heading for the disaster of Fischli and Weiss’s film, by staking a claim to its nature and shouting “It’s the way we are made”, the contemporary response of the objects themselves to the original title The Way Things Go.

Hello

Can you let me know how long the way things do exhibition is on until?

Thanks a lot

Doj

Hello Doj,

The exhibition The Way Things Do is on view until 1st October. Here you can check the information: https://www.fmirobcn.org/en/exhibitions/5723/the-way-things-do

Thank you very much for your interest. Kind regards.