On the occasion of the Éluard, Cramer, Miró – À toute épreuve, more than a book exhibition, Dolors R. Roig examines the creative process behind the book by Joan Miró based on a collection of poems by Paul Éluard, explaining how Miró ventured beyond illustration and how the collaborative project led to new poems. While reviewing this creative adventure, her article addresses the way in which Éluard’s and Miró’s imaginations merged.

Dolors R. Roig holds a PhD in Art History and specializes in modern and contemporary art. She is responsible for art research and programming at Galeria Mayoral and teaches at the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, where she was involved in the Joan Miró: An Artist Who Defined a Century MOOC and the Miró Studies Postgraduate Diploma.

À toute épreuve and the Art of Language

In his Epistle to the Pisos, the lyric poet and satirist Horace[1] coined the expression ‘Ut pictura poesis,’ which literally means ‘as is painting, so is poetry,’ or, in other words, ‘poetry resembles painting.’ Aside from what Horace may have intended – to establish that poetry was like painting, and thus an imitation of reality, but through the use of words-, the Latin expression per se has a direct, timeless connection with Miró’s view: ‘Je ne fais aucune différence entre peinture et poésie’ (I make no distinction between painting and poetry). On the other hand, if we look up the word poesia (poetry) in the Institut d’Estudis Catalans dictionary, we find a definition that would translate as follows: ‘The art of language that consists of using rhythm, usually that of verse, to express one or several subjects, an idea, a feeling, etc., which each poet strives to endow with a value that is at once unique and universal.’ Therefore, bearing in mind this definition and Miró’s statement, we can draw the following conclusion: if poetry is the art of language and Miró made no distinction between painting and poetry, we could say that Miró’s painting is also the art of language.

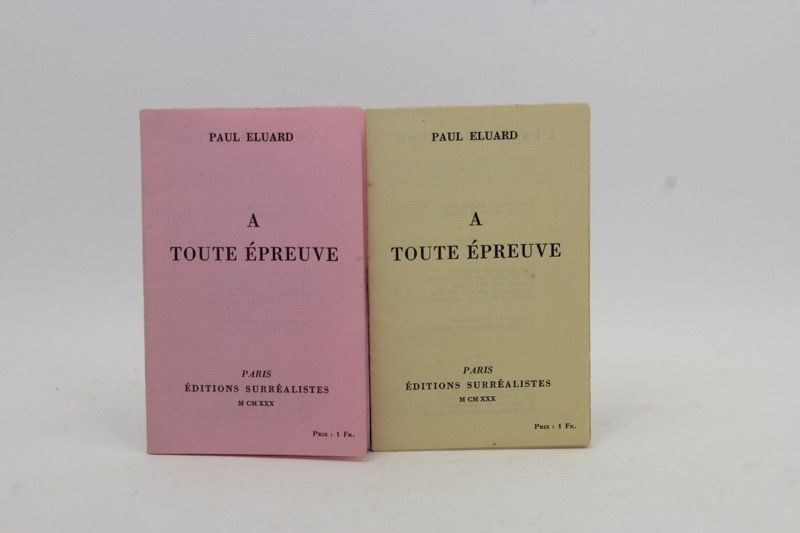

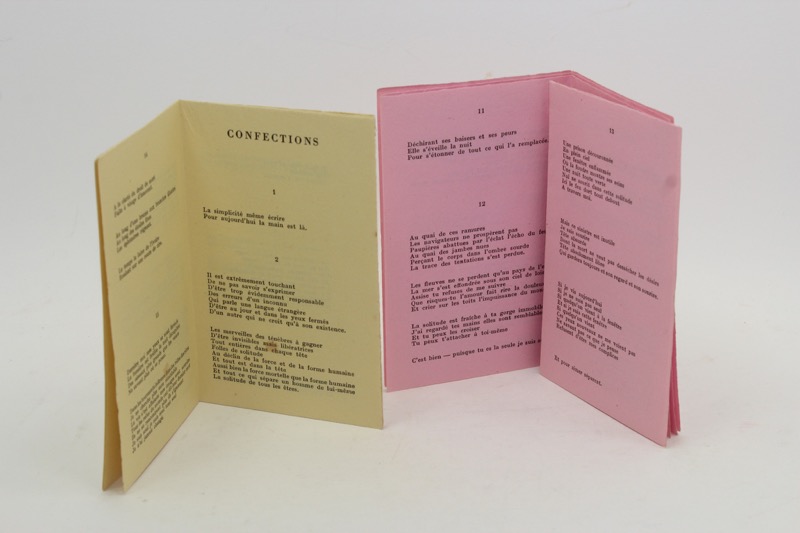

In 1930, right after Gala had left him, the Surrealist poet Paul Éluard wrote a series of three poems (‘L’Univers-solitude’, ‘Confections’ and ‘Amoureuses’) gathered in a booklet titled À toute épreuve and published by Éditions Surréalistes. It was sixteen pages long and had no images accompanying the text.

À toute épreuve first edition by Éditions Surréalistes

Between the À toute épreuve from 1930 and the edition showcased in the exhibition, twenty-eight-years had elapsed, and the basic difference between the two publications is the step from a single author – the poet Paul Éluard -to the inclusion of two other people: Gérald Cramer (the publisher) and Joan Miró (the artist-poet), the perfect ménage à trois for a literary metamorphosis.

Éluard, Cramer, Miró – À toute épreuve, more than a book exhibition room

What we see here is a transformed book whose conception, while maintaining the same original poems from 1930, resulted in a new book that became an experience for the senses. And this final outcome is hardly surprising, given that Miró, who had already been thinking of a possible collaboration with Éluard, (‘[…] I could publish a collection of colour prints, either engravings, woodcuts or lithographs, like a book or a folder, with a poem by Éluard.’[2]), became the essential ingredient in the metamorphosis.

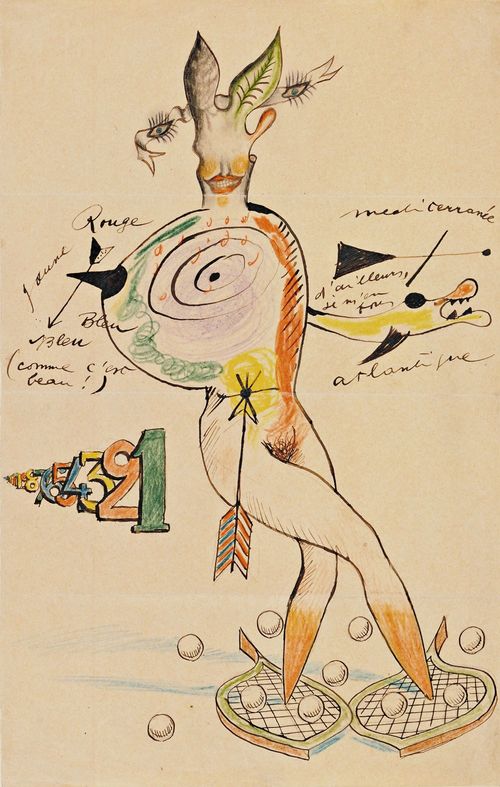

Miró was a firm believer in artistic collaborations, and the more they let him play with chance and his imagination, the better. There were all sorts of collaborations: with literature, sculpture, ceramics, painting… For example, in the Cadavre Exquis titled Nude (1926-27), in the MoMA collection in New York, Joan Miró was the second hand, preceded by Yves Tanguy and followed by Max Morise and Man Ray. Cadavres Exquis was a Surrealist game that consisted of three or four people taking turns to produce a joint drawing. The paper was folded as many times as there were participants, in such a way that each artist could not see what the former had drawn. The final outcome was always fortuitous, unpredictable and, above all, Surrealistic, arising from its participants’ imaginations. They are assemblages of imaginations, in which the initially unrelated pictorial hands come together to create a new, extraordinary form. The imagination that Joan Miró conveys in Nude reveals the artist’s poetic drive, and includes words to accompany the drawing: [Rouge / Jaune / Bleu / Bleu / (comme c’est beau!) / mediterranée / d’ailleurs, / je m’en / fous / atlantique]. The result is a poem-drawing aligned with the peinture-poèmes of the 1920s.

Untitled “Cadavre Exquis”. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase, 1935

À toute épreuve, an assemblage of imaginations: Éluard’s, Cramer’s and Miró’s. À toute épreuve, a poetic assemblage: that of Éluard’s poetry and of Miró’s visual (?) poetry. The question mark is intentional. Did Miró make illustrations for Éluard’s poems or visual poetry based on Éluard’s poems?

The answers are sure to vary depending on one’s point of view, but they all emerge from a common element: experiencing the book.

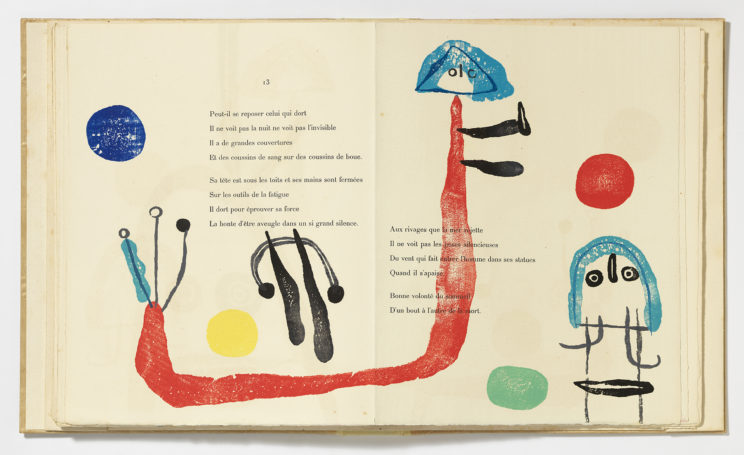

In his essay on À toute épreuve,[3] Christopher Green poses the following question: ‘[…] Is this a book that demands to be viewed before it is read, or vice versa?’[4] The author finds the answer in an analysis provided by Anne Hyde Greet[5] in which she states that ‘Miró responded to his reading of the poems, so reading is primary.’[6] Green first mentions that ‘But the merest glance through the book is enough to see that viewing can actually precede reading, or at least can have parity with it,’[7] and then adds, ‘[…] Miró was responding not primarily to the poems as such but to typography, and finally to his own image-making.’[8] He then states that ‘viewing can actually come before and open up new readings of the poems, can transform them.’[9] Clearly Miró does not simply illustrate Éluard’s poems (if we consider illustration as ornamentation, decoration, a visual complement to what is told in the verses of the poem), but rather his pictorial action leads to new poems, making Éluard’s poems change into different ones – a fact that can be confirmed if one first reads Éluard’s poems[10] as they were originally conceived in 1930 (with no accompanying images) and then reads the 1958 edition of À toute épreuve produced jointly with Cramer and Miró. On pages 76 and 77, the verses merge with Miró’s drawings in a subtle but absolutely deliberate signal to the readers that they are reading both written and visual poetry at once.

Miró interprets Éluard’s poems; he makes them his own, internalizes them, thinks about them, feels them and transforms them into images, into visual poems that heighten the voice of Éluard’s soul and imagination but also become the voice of Miró’s imagination. These two imaginary worlds complement each other and, aside from a dialogue, become the art of language: they are poetry.

[1] Quintus Horatius Flaccus (65 BC Venusia – 8 BC Rome)

[2] Miró, Joan. [Notes, 1941-42]. Fundació Joan Miró Archive.

[3] Between the 1930 edition and the one published in 1958 there was a long process comprising many different stages. Christopher Green offers an exquisite analysis and study of the complete book in his recent Éluard, Cramer, Miró. ‘À toute épreuve’, more than a book (Miró. Documents).

[4] Green, Christopher. Éluard, Cramer, Miró. ‘À toute épreuve’, more than a book. Barcelona: Fundació Joan Miró (Miró. Documents), 2017, p. 59.

[5] Hyde, Anne. Miró, Éluard, and Cramer: À toute épreuve: A Collaboration Between Artist, Poet, and Publisher. New York: George Braziller, 1984.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Green, Christopher. Op. cit., p. 59.

[8] Ibid., p. 60.

[9] Ibid.

[10] ‘L’Univers-solitude,’ ‘Confections’ and ‘Amoureuses’ (date of access: 28/04/2017).