Santos M. Mateos, who defines himself as a museophage and exponaut, takes a global look at means of communication in museums, inviting us to reflect on the shift in focus that has occurred in recent years.

Getting Museums in Tune with Their Visitors

Museums have numerous different kinds of visitors, although this rich multiplicity is gradually becoming polarized and splitting into two main types, rather like a caricature: those who consider museums to be a sort of religious temple and those who visit them as if they were theme parks. With good reason Mikhaïl Piotrovsky, the director of the Hermitage, defined museums as “institutions midway between Disneyland and the Church”.

At museums where both groups converge, there is friction. Museums cannot keep the first group happy without frightening off the second and vice versa. Finding a balance is a major challenge: how can those occasional visitors be made to come back without losing the museum’s regulars?

To transform trips to museums into knowledge-based adventures of discovery, capable of making a profound, long-lasting cultural impact (Mikel Asensio and Elena Pol), as well as ensuring return visits (the true road to success for museums, Jorge Wagensberg), one indisputable fact must be taken on board: without visitors, museums lose their status as such and become mere warehouses. Thus it is time for museums to devote the same attention to visitors as they do to their collections, leaving behind models where visitors are treated like strangers or guests (Zahava D. Doering).

With this as our premise, it is important to note that museums are an artificial habitat for visitors where they are required to comply with a whole series of behavioural rules (like the classic “do not touch the works on display”, “do not take photographs with a flash” etc.). Although regular visitors know and generally observe these rules, it is normal for occasional visitors not to be aware of them, hence their failure to observe them. When this occurs, it is a problem for museums and action must be taken instead of just complaining about it. Complaining is easy and psychologically gratifying, but it is no use if it is not accompanied by efforts to rectify the situation.

To do so, museums must have a department devoted to planning even the most minimum details of the areas open to the public so as to guarantee an enjoyable enriching experience for them in sustainable circumstances for the museum. Clues as to what this kind of department should be like can be found in the world of haute couture (the idea is developed here) and its petites mains.

For museums to attend to visitors properly, some points must be considered that have a direct impact on their interaction with the items on display and, ultimately, on the encouragement of sustainable relations. In conjunction with other managerial measures, such as control over the museum’s carrying capacity and visitor flows, communication is a valuable tool in ensuring mindful visitors (Gianna Moscardo).

Preventive dissemination is another means of working toward sustainability (Mateos, Marca and Attardi). Preventive conservation and risk management can be used in association with heritage interpretation as part of an awareness-raising strategy to inform and convince visitors of our heritage’s extreme fragility. The end goal is very clear: to influence visitor attitudes and to promote collaborative respectful behaviour.

Through different forms of communication, preventive dissemination can be used as a tool in preventive conservation and corporate communication, influencing the behaviour that is expected of visitors, while also drawing attention to the efforts that are dedicated to the conservation of our museums’ heritage.

For instance, if certain items are not to be touched, the typical ‘do not touch’ pictogram is unlikely to be successful. In a cultural and educational centre like a museum, the best option will always be to explain why they should not be touched. To do so, messages can be created in small doses of information, ranging from the purely informative to more creative approaches.

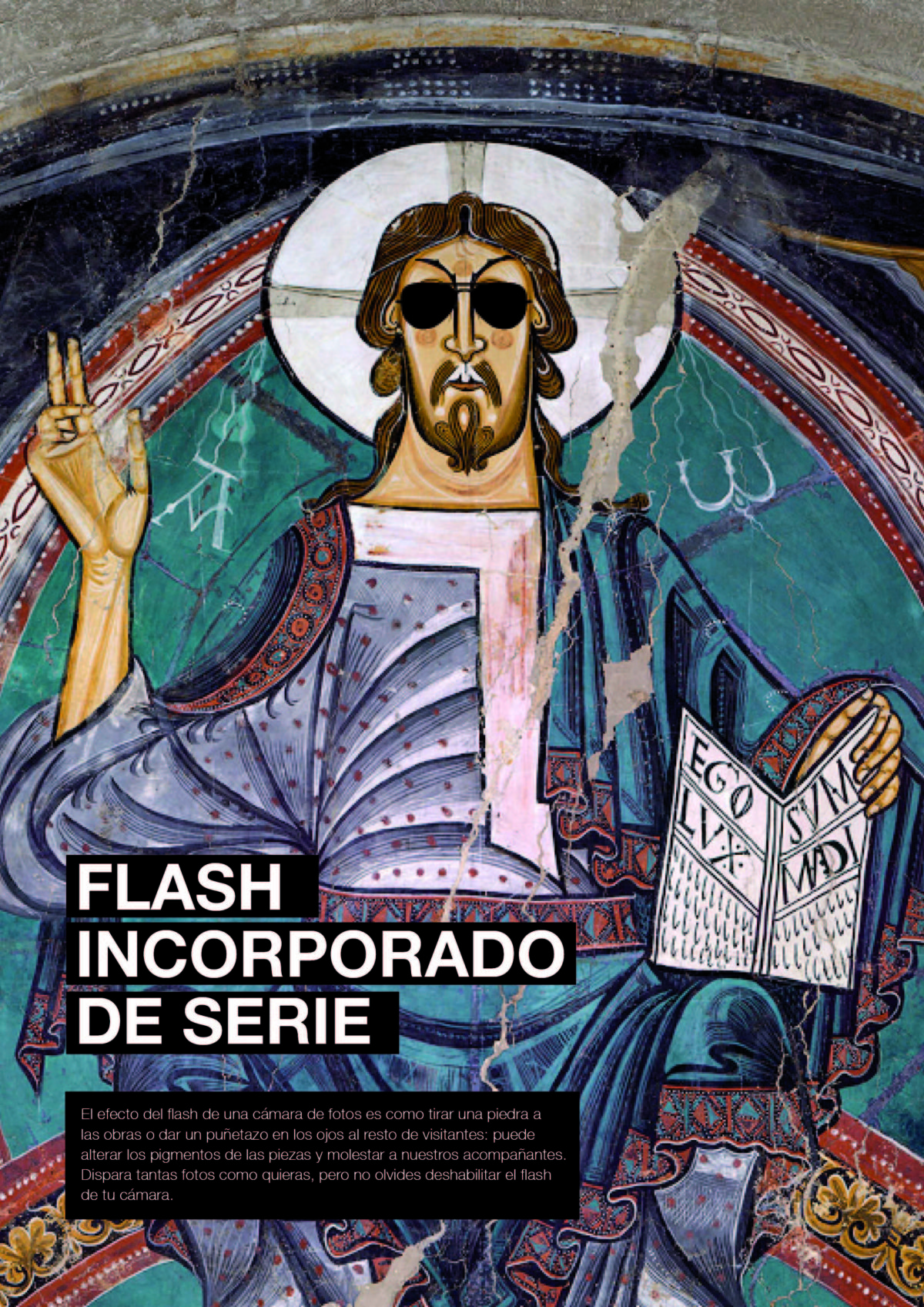

In this example of preventive dissemination, a simulation created for the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, a creative message was designed to stop visitors from taking photographs with a flash in the Sant Climent de Taüll Room. Source: Mateos, Marca and Attardi.

The Joan Miró Foundation in Barcelona also serves as an example to illustrate the type of communicative initiative that can be taken to offer visitors an insight into the work of professionals from the fields of preventive conservation and restoration. During the onsite restoration of the tapestry by Joan Miró and Josep Royo, from March 8th to 11th 2019, visitors could actually see it being worked on.

Once the work was over, from March 26th to May 12th 2019, visitors could see the back of the tapestry by walking round it as if it were a sculpture.

Visitors clearly find this kind of thing very interesting. They like to see and be given an explanation about things that are normally not seen or explained. This is called curiosity and it is one of the driving forces behind our species. At the same time, this kind of initiative raises people’s awareness of the work involved in preventive conservation and restoration, offering a clear insight into the efforts that museums make to conserve their collections.

If museums take on board the fact that they are very powerful communicative tools and that they need to get on the same wavelength as visitors, they can make the public revisit them. It is not an easy challenge, but it is a fascinatingly interesting one.