In this article, Dolors Bramon, a historian with a PhD in Semitic languages, takes a historical look at the conflict between different cultures in Spain inaccurately referred to as convivencia. The author questions the honesty of the meaning of multiculturalism and underscores the need for repairing historical injustices. As in Kader Attia’s work, for Dolors Bramon scars are cries against oblivion.

Scars and Reparations

In a world that we believe to be so globalized and multicultural, it was about time that someone reminded us of the scars we still bear. Multiculturalism does not mean that everyone accepts the plurality of cultures, and it is obvious that in Kader Attia’s life there have been a few. North Africa and Europe, so close to one another, have clashed in the course of history leaving scars that have yet to be repaired.

Kader Attia. Humiliation, 2018. Site-specific wall sculpture; carving. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Pere Pratdesaba © Kader Attia, VEGAP, 2018

The label of La España de las Tres Culturas – the Spain of three cultures – has been used to sell us an idea that falls to pieces when we think back to our past. Jews, Christians and Muslims living in harmony! The historian Américo Castro[1] sparked the controversy about how the lives of the members of these three religious and cultural groups unfolded in the Middle Ages: was it convivencia[2], coexistence or convenience?

Castro’s portrayal of harmonious relations was criticized by David Romano,[3] who suggested replacing the term convivencia with coexistencia. Now, according to Brian Catlos,[4] there is no doubt but that what emerged in the Spanish medieval world was

“the dynamic of utility from the perspective of both the dominant and the dominated groups. As occurred in other similar situations in Europe, and even in the modern world, the relationship was primarily based on a perception of utility among some groups as regards others, and was no more, and no less, than a case of convenience.”

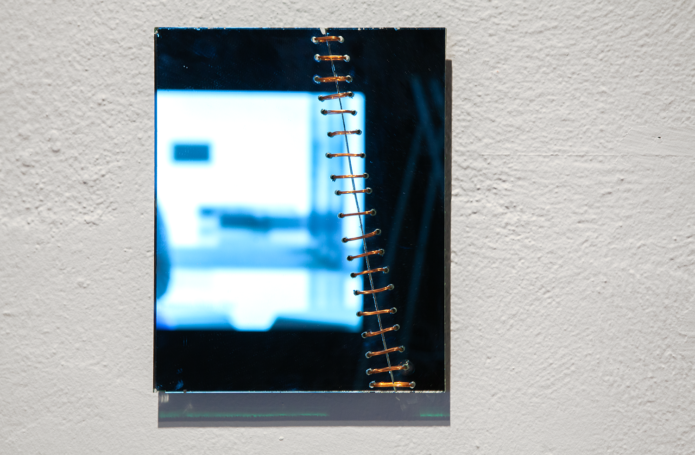

Kader Attia. Untitled, 2018. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Pere Pratdesaba © Kader Attia, VEGAP, 2018

It is all fine and good to speak of reparation, but it so happens that in the modern world it has not yet occurred. The fact is that the Spanish Jews were expelled in 1492 and many of them settled in North Africa – in other words, in Islamic lands. Centuries later, a royal decree issued on 20 December, 1924, sanctioned by Primo de Rivera’s military Directorio, proposed that Spanish citizenship be granted to

“those formerly protected (sic!) by Spain or their descendants, and, in general, individuals belonging to families of Spanish origin who at some point were registered as Spanish citizens, and these Hispanic individuals, with a deeply-rooted love for Spain, have not succeeded in obtaining our citizenship due to lack of knowledge of the law or to other causes unrelated to their desire to be Spanish.”

The decree was actually intended for people who could provide proof of their Jewish ancestry – that is to say, Sephardic Jews. Although only about 3,000 seized the opportunity, this was the legal framework that allowed several Spanish diplomatic missions to protect Sephardic Jews during World War II, saving thousands from the Holocaust. Doctor and Senator Ángel Pulido played a prominent role in defending the Sephardic group, also supported by other intellectuals such as Pérez Galdós, Unamuno and Menéndez Pelayo.

But what happened with the remaining Muslims?

Kader Attia. Intifada: The Endless Rhizomes of Revolution, 2016. Installation. Metal sculptures, rubber, stones, newspapers, photocopies. Courtesy of the artist, Galerie Krinzinger and Galerie Nagel Draxler Berlin / Cologne. Photo: Pere Pratdesaba © Kader Attia, VEGAP, 2018

In 2006, the president of the Junta Islámica de España, supported by two political parties, Izquierda Unida and the Partido Andalucista, requested that the Andalusian Parliament call on the Spanish government to grant Spanish citizenship to descendants of Moriscos –the Spanish Muslims who had been baptised by force in the first half of the sixteenth century and were also expelled between 1609 and 1614. Some of them lived, and continue to live, in several North African countries such as Morocco, Algeria, Tunis, Libya, Mauritania and Mali, and in former Ottoman lands such as Salonica or Istanbul. There are North African families that preserve the memory of their past – as we can see, for example, in the main square of Tozeur, in Tunis, where the exposed brick buildings and an unusual clock on the minaret of a mosque clearly replicate a square in any Aragonese town.

This effort sought reparation for the way in which the history of the Moriscos had fallen into oblivion and reminding us that they ought to receive the same treatment as the Jews. The initiative could move forward if the article in the Civil Code that acknowledges the preferential right of Sephardic Jews were changed to include the descendants of Moriscos, also of Spanish origin.

But scars do not fade without equal reparation.

Translated by Deborah Bonner

[1]España en su historia. Cristianos, moros y judíos. Barcelona: Grijalbo, 1948.

[2] The term convivencia (the state of living together in harmony), used in a broad sense in Spanish, was specifically coined by nineteenth-century Spanish historians to describe, according to their somewhat idealized perception, the religious tolerance and cultural exchange that occurred between Muslims, Jews and Christians from the Muslim invasion (711) to the expulsion of the Jews (1492) and the end of Muslim rule.

[3]“Coesistenza/convivenza tra ebrei e cristiani ispanici”. Sefarad (Madrid-Granada), 55 (1995), pp. 359-382.

[4]Cristians, musulmans i jueus a la corona d’Aragó. Un cas de conveniència”. L’Avenç (Barcelona), 263 (2001), pp. 8-16.