Writer and journalist Sergio Vila-Sanjuán was curator of the 2005 Barcelona Year of Books and Reading. In this article, originally published in Carnet magazine and reprinted for this year’s Saint George’s Day, he explores the connections and overlaps between the world of books and the world of art.

Cultural Connections

Art in Books

As aptly noted by Ingo F. Walther and Norbert Wolf, medieval illuminated manuscripts, with their rich colours and precise details—what we might call their majestic, noble air—exert a growing fascination on present-day readers. Over the past fifteen years, a slew of major exhibitions in cities such as New York, London, Vienna, Milan and Heidelberg have attracted hundreds of thousands of visitors to wonder at these manuscripts.

Codex Aureus of Lorsch. CristianChirita, Wikimedia Commons.

The books themselves have wonderfully evocative titles, including the Coronation Gospels of Aachen, the Utrecht Salter, the Codex Aureus, the Berthold Sacramentary, The Art of Falconry by Frederick II, and the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, among others. Taschen has recently published a highly recommendable comprehensive companion to them: Codices illustres: The World’s Most Famous Illuminated Manuscripts, 400 to 1600, by the aforementioned Walther and Wolf. It features a wealth of examples by virtuoso miniaturists and illuminators in meticulous detail depicting not only religious settings but also court scenes and snatches of everyday life that illuminate and expound upon the accompanying texts. All these manuscripts contain the germ of the idea of the illustrated book, which has branched out and blossomed into the many different varieties we know today.

Romantic Novel, Santiago Rusiñol, 1894. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

Books in Art

Depictions of books in art also date back a long way. Images of readers can be found in Hellenic and Roman antiquity, but it is above all in the Middle Ages that books began to occupy a place of honour as iconographic objects. Narcís Comadira’s study of books in artwork at the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, La paraula figurada. La presència del llibre a les col·leccions del MNAC (Figurative Words: The Presence of Books in the MNAC Collections), together with the catalogue of his selection, offers a remarkable insight into this phenomenon. Christ in Majesty holding the Book of Life in the apse of the Seu d’Urgell cathedral as a symbol of everything holy, Saint Matthew writing in the apse of Pedret, and Saint Jerome in his study among books and writing implements painted by Jaume Ferrer, to name but a few. Not to mention Quentin de la Tour’s famous reader, Ramon Martí Alsina’s sleepy reader, Lluís Graner’s portrait of art critic Casellas working at his desk, and Santiago Rusiñol’s painting of a young middle-class woman reading a romantic novel by the fireplace. The book is a recurring image in Western art, which has steadily imbued it with different meanings over time: holiness, individuality, social status, gender interests, etc.

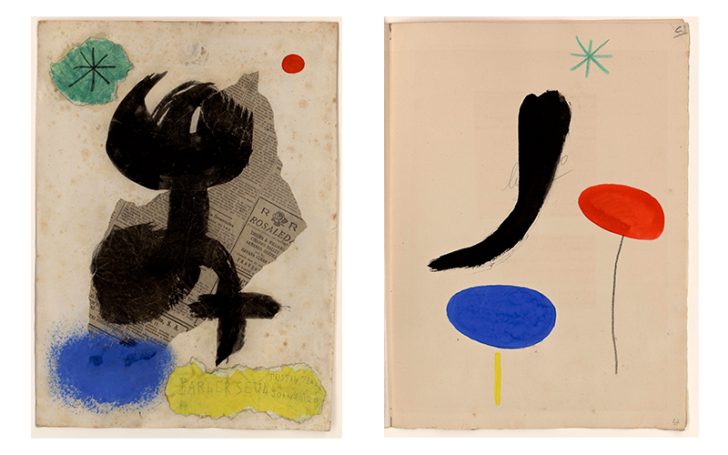

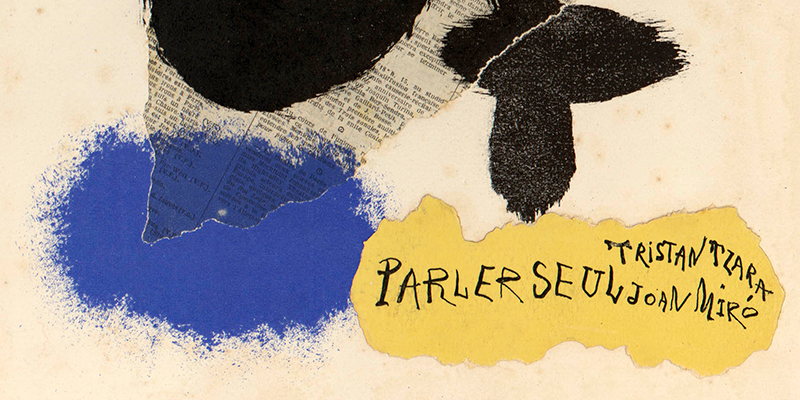

Mockup of Parler seul, a book of poems by Tristan Tzara illustrated by Joan Miró. 1948–1950.

Miró, Books and Art

In the early 20th century, the avant-gardes burst onto the scene in a hitherto unknown alliance: writers and visual artists working together as equals in groups sharing a whole series of cultural concepts. This partnership gave rise to artist’s books that went beyond the traditional concept of an illustrated book. As shown by the organisers of the exhibition Joan Miró: The Architecture of a Book, Miró not only illustrated poems by the likes of Tristan Tzara, Paul Éluard, Joan Brossa and Rafael Alberti but also “conceived painting and poetry as an indivisible whole and sought to materialise this aspiration through a love of books”. Through drawings, mockups and plates from his books, from his correspondence with writers and publishers, in his work with classic texts, we can get an idea of how Miró’s invigorating spirit—along with several of his keen contemporaries, above all Picasso—revamped traditional depictions of art in books and books in art. Books would no longer merely illustrate a text but would be created on an equal footing with it; rather than representing or being represented by something, they would be an art object in themselves. The consequences of this new vision can still be felt today.

Sergio Vila-Sanjuán

Curator of the 2005 Barcelona Year of Books and Reading