Miró dreamt of a large studio. At one point or another, all artists have dreamt of a large studio – a creative space that would enable them to build their utterly personal microcosm. Coinciding with the exhibition Shared Studios. Three Case Studies, which explores the experiences and affinities of artists working in the same space, we wanted to look back at one of Miró’s first studios, in the Paris of the 1920s, at 45 Rue Blomet.

Rue Blomet, a Space for Poetry

In February 1921, one hundred years ago, Joan Miró moved to Paris, into a studio he rented from Pablo Gargallo at 45 Rue Blomet. With its museums, its cultural effervescence and its literary gatherings, the city overwhelmed and paralyzed Miró. “I barely do any work here; it’s impossible. I feel that a new world is opening up in my brain.” He was ushered into this new world by his neighbour from the studio next door, the painter André Masson.

Miró first met Masson at the Café de la Savoyarde shortly after he arrived in Paris. Masson recalled the moment as follows: “[…] it at was at La Savoyarde, a café right below the Sacré-Coeur, that Joan and I met for the first time. […] we walked straight up to each other and felt a mutual understanding right away. We were also surprised to find out that we had both just rented studios at 45 Rue Blomet.”

Over the months they were there, Masson and Miró became close friends, and Miró started spending time with many of the poets, artists, and writers that impressed him so, including Roland Tual, Michel Leiris, Antonin Artaud, Armand Salacrou and Georges Limbour.

They all viewed Masson as their mentor, given his extensive erudition and his harrowing experience as a soldier during the First World War. Miró recalled those times in an interview with James Johnson Sweeney: “Masson was in the studio next door. He was always a great reader and full of ideas. Among his friends were practically all the young poets of the day. Through Masson I met them. Through them I heard poetry discussed. The poets Masson introduced me to interested me more than the painters I had met in Paris. I was carried away by the new ideas they brought and especially the poetry they discussed. I gorged myself on it all night long – poetry principally in the tradition of Jarry’s Surmâle.”

“Rue Blomet was a decisive place, a decisive moment for me. It was there that I discovered everything I am, everything I would become.”

For Masson, 45 Rue Blomet was also a space for leisure, and their friendship was anything but intellectual: they shared meals, talked, listened to music, danced, and worked driven by a common spirit.

Miró engaged in this atmosphere both from his own studio and from Masson’s. The doors were always open, and a hole in the dividing wall further contributed to their connection.

Miró’s work discipline was entirely different from his neighbour’s: “I was a maniac of order and cleanliness […] I liked to leave my monk’s cell and go to the studio next door, with its unbelievable clutter of papers, bottles, canvases, books, and household objects. […] Masson worked feverishly. Listening to music, in the midst of loud conversations. I could only work alone and in silence, with ascetic discipline […]”.

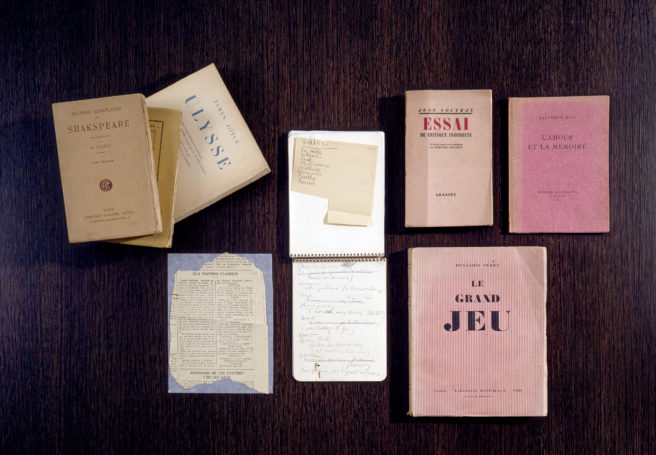

Books and notebook from Joan Miró’s personal library

© Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona. Photo: Jaume Blassi

In Joan Miró’s personal library, held at the Fundació’s archive, we find many of the books that were talked about in those gatherings and by the poets attending them. Miró, always methodical, listed the books that had been discussed in his notebooks and crossed them out when he had managed to read them.

However, although Rue Blomet was a meeting place for friends and colleagues who discussed painting, theatre or literature and played chess, darts, or cards, it was – for most of the group, and especially for Miró – a journey of initiation and personal growth.

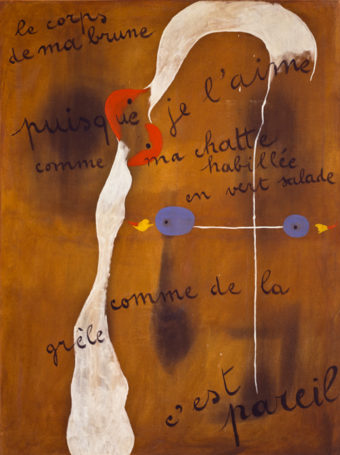

Poem-painting (“Le corps de ma brune puisque je l’aime comme ma chatte habillée en vert salade comme de la grêle c’est pareil”). Joan Miró, 1925 © Successió Miró, 2021

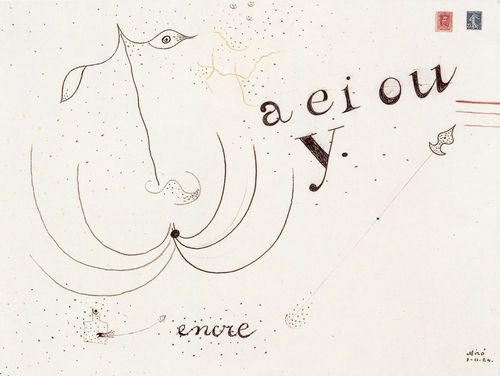

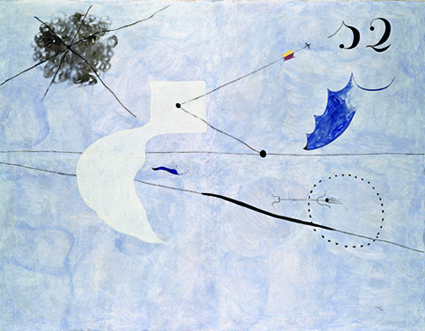

The spirit of rebellion in the atmosphere at Rue Blomet gave Miró the freedom to use all sorts of images: personal and borrowed, poetic and scatological, magical and trivial. In the process of stylization and transformation that unfolded in Miró’s work beginning with The Farm (1921-22), with The Tilled Field the artist succeeded in shedding all conventions and took his painting to an unprecedented state of freedom. His output ceased to perform a descriptive function, acquiring a symbolic character that was reinforced by the introduction of letters and numbers, first simply as appealing visual elements (Untitled, 1924) and gradually gaining symbolic and expressive value (Poem-painting (“Le corps de ma brune puisque je l’aime comme ma chatte habillée en vert salade comme de la grêle c’est pareil, 1925).

“I make no distinction between painting and poetry”

Encountering the poets and poetry – as a literary form – allowed Miró to find new ways to move beyond painting. They all agreed on the importance they attributed to poetry. “[…] for us, poetry, in the broadest sense, had a value that it would not be an exaggeration to qualify as sacred […].” “Poetry, both for Joan and for me [Masson], was of the utmost importance. Our ambition was to become poet-painters […]”.

Untitled. Joan Miró, 1924 © Successió Miró, 2021

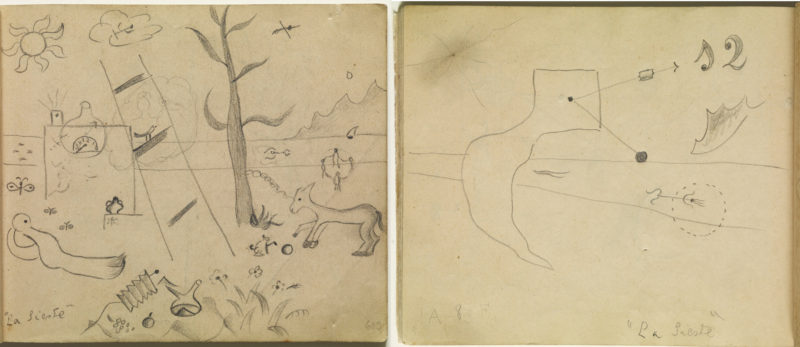

In Miró’s work, poetry was the distillation process that he applied to his pieces. He went from the accumulation of anecdotes to symbolic representation by slowly and reflexively stripping away the superfluous, as we can see in works such as La sieste, Peinture “48”, and Untitled. These pieces are not the result of the mimesis of another painter’s gesture, nor of Miró’s reading of poets, nor of a random mirroring; they involve a slow creative process of poetic emulsion that gradually introduces all these ingredients, arising from an inner quest for synthesis which succeeds in taking painting to a level of lyricism eloquent enough to blur the boundaries between painting and poetry.

Preliminary sketches for The Siesta. Joan Miró, 1925

La sieste. Joan Miró, 1925 © Successió Miró, 2021

While in The Farm the virtuosity of detail taken to the extreme led Miró along the path to stylization, it was poetry – in the most etymological sense of the word – that opened the door to an endless world of signs and constellations.

In 1926, Miró left Rue Blomet and moved across the Seine to the rive droite, into a new studio on Rue Tourlaque, and the next year Masson followed him. Miró realized it was the end of an era: “Rue Blomet: everything that moved there did not belong to this world. What happened? Have we come down to earth? I can’t resign myself to believing we’re so lost.” Michel Leiris also recalled the moment when their meeting place on Rue Blomet disappeared. “Does that mean that it ceased to exist? Yes, if we consider that […] it only made sense that we would all go separate ways. And no, if we take into account the trend […] that I continue to represent,” although from that moment on, the story of the people who made up that group was intertwined with the history of Surrealism.

Miró also carried those memories with him for many years. They came up in the interviews he gave throughout his entire life and left their visual mark in Peinture (“48”) from 1927. This piece, executed after he left Rue Blomet, shows a large number 48 in the lettering used in the sign that Miró saw every day across the street from his studio.

Peinture-Poème («48»). Joan Miró 1927 © Successió Miró, 2021

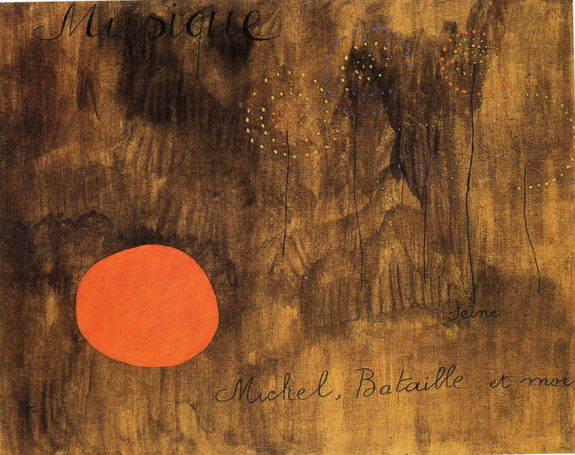

Miró stayed in touch with many of the poets from the Rue Blomet circle, but especially with Michel Leiris and Georges Bataille, two of the founders of the journal Documents and both fairly critical of Breton. The Poem-painting (Musique, Seine, Michel, Bataille et moi), from 1927, bears witness to that friendship: the only piece that refers to the artist’s biography, it evokes three friends, three poets, three makers of images walking together at night along the Seine.

Bibliographical references:

Epistolari català. Joan Miró 1911-1945. Editorial Barcino/Fundació Joan Miró, 2009

« A Joan Miro pour son anniversaire » dins d’André Masson, Le rebelle du surréalisme. Ecrits, Collection Savoir

ROWELL, Margit (ed.). Selected Writings and Interviews. New York: Da Capo Press, 1992.

LEIRIS, Michel “45 Rue Blomet” [1982], in Los Cuadernos del Norte.