Coinciding with the presentation of the Miró – ADLAN. An Archive of Modernity (1932-1936) exhibition at the Fundació Joan Miró, we are publishing the following interview with Teresa Montaner, the head of collections who is also responsible for the Fundació’s archive.

The Fundació Joan Miró Archive: Awareness of and Responsibility for a Legacy

Emotion and Respect

One enters the Fundació’s archive quietly, almost on tiptoe. Not because there are any rules to that effect – simply because you know you are stepping into the artist’s most intimate realm. Teresa Montaner has been in charge of the archive for years, and recounts the first time she had access to Miró’s “papers” thanks to the Fundació’s then director Rosa Maria Malet and head of conservation Carme Escudero.

She knew Miró from his finished work, as it was presented at university within the syllabus for the overall history of modern art, and also the Miró she had seen in museums. At the time, Alexandre Cirici had already referred to Miró’s papers, Gaetan Picon had published the Carnets Catalans and Pere Gimferrer was writing The Roots of Miró, but in the university, artists were rarely approached in terms of their work processes. “Discovering Miró through his drawings was thrilling, because I didn’t know that these documents even existed and because I realized at the time that I was encountering his seminal output. I also felt enormous respect for the artist, for his having taken the trouble to save his sketches throughout his life despite the experiences he had to face, with wars and many changes of residence and studios; and gratitude, for his having given this vast legacy to the Fundació and to the world.”

Awareness of a Legacy

In 1911, at the age of eighteen, Miró wrote to his parents, convinced that someday he would “hold a good position in painting.” As we know from this statement, Miró was certain that he would eventually play an important role in painting and in society. In the speech he delivered in 1979 when he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Barcelona, he spoke of his “special civic responsibility.” An artist, according to Miró, “is someone who, as others remain silent, uses his voice to say something, and is obliged to have it not be useless, but rather something that can be of service to mankind.”

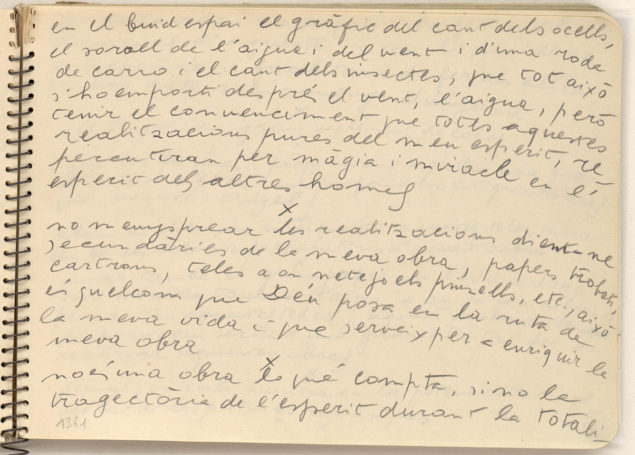

Notes. c 1942, Fundació Joan Miró.

May this awareness of wanting to transcend by offering “a service to others” have been the reason why Miró was able to keep all his drawings, letters, and documents so carefully over time and in varying settings?

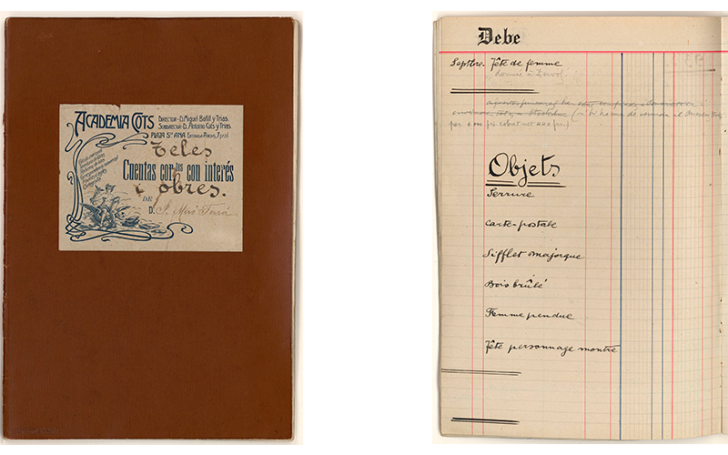

“I think the reasons are many. Clearly the urge to transcend is there; it’s part of our culture. In 1931, for example, Miró started keeping a logbook where he wrote down titles, dates, and in some cases the name of the owner in whose hands the piece had ended up. That same year, shortly before Picasso opened his first retrospective in Paris and Zervos started working on a catalogue of his entire output, Miró wrote to his friend Josep Francesc Ràfols, with whom he had kept an extensive correspondence, asking him to keep all the letters they had exchanged, because they could be important in the future. When years later Jacques Dupin set out to write Miró’s biography, the artist guided him to the letters he had shared with his friends, an indication that he had that conviction of becoming important in the art world someday. Keeping his drawings and notes was a way of maintaining an inventory of his painting up until the day that a full catalogue would be produced. In addition, it was a tool that allowed him to review his work. Whereas now we find Miró’s most important paintings in museums around the world, at that time most of his pieces ended up in private collections and the artist lost sight of them.”

Notebook cover and notes. 1931, Fundació Joan Miró.

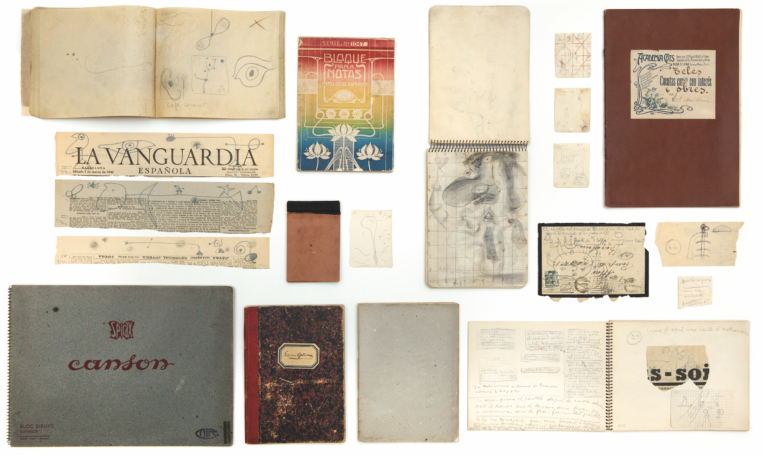

The Fundació’s archive, set up at Joan Miró’s request, now holds close to ten thousand documents from all the stages in his career, ranging from preliminary sketches to notes, mock-ups, correspondence, and a broad range of documents. It also comprises an almost complete collection of Miró’s lithographs and other prints, including some of his artist’s proofs and the illustrated books that resulted from his close connections with several poets and his desire to push the boundaries of painting. All these holdings are now kept in flat file cabinets, boxes, and conservation sleeves, all inventoried and classified.

“This collection arrived in Barcelona from Miró’s studios in Palma de Mallorca. The first donations are from June 1975 and April 1976, coinciding with the opening of the Fundació. The second was made in November 1987, after the artist’s death. Over the years, the Fundació’s documents collection has grown with donations and loans from private owners and Miró’s family and friends. Among these items, I would highlight some very interesting collections of letters, as well as the artist’s personal library. These holdings are a reflection of who he was and how he thought.”

Thinking by Drawing

When touching on the subject of Miró’s way of thinking, Teresa’s words become filled with passion. This collection not only gathers the artist’s preparatory sketches and drawings, but also an important part of Miró’s thought. “Particularly, we have reflections written in his notebooks from the 1940s. These are thoughts that Miró wrote down in Mallorca and Mont-roig, where he lived inconspicuously from the time he had decided to return from exile when the Nazi forces invaded France. Miró talks about his spiritual retreat, about how to face the present situation, about not worrying if a piece was left unfinished because what really mattered was not the piece itself, but the path of an entire lifetime and the impact it would have on others. The collection of drawings and documents dating up until the 1950s and now held at the Fundació was carefully selected by the artist. It consists primarily of sketchbooks, but from most of them he only kept the last drawing. Miró mentioned in several interviews that in 1956, when he decided to settle permanently in Palma de Mallorca where his friend Josep Lluís Sert had designed a studio for him, he went through a period of severe self-criticism and destroyed many of these drawings. Those that he did afterwards reveal his work method, with many more sketches for each single work, and countless projects that were never carried out.”

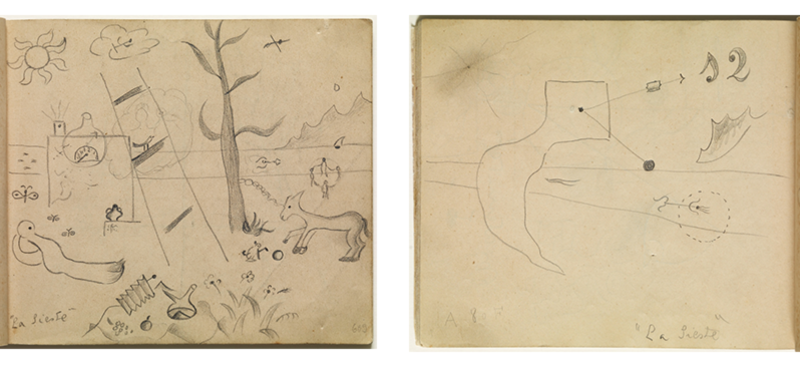

Preliminary drawings of La sieste (The nap), 1925, Fundació Joan Miró.

Work and Method

We ask her which pieces she finds particularly relevant. “All of them, as a whole! The sketchbooks from the 1920s and 30s come to mind, the ones that led Carolyn Lanchner to highlight Miró’s method of working in series. But even the drawings for pieces that never materialized are important; every one of them carries with it a shock factor that he uses as a stimulus to achieve new goals. I think of the sketchbook he left behind in Barcelona when he went into exile to Paris in 1936, and which, for a short time, prevented him from moving ahead with his painting. Or the Varengeville sketchbook, which he thought he had lost on his trip back to Catalonia, and which he drew again from memory. He never implemented it, but I’m sure that the fact of reconstructing it helped him gain awareness of the moment he was experiencing.”

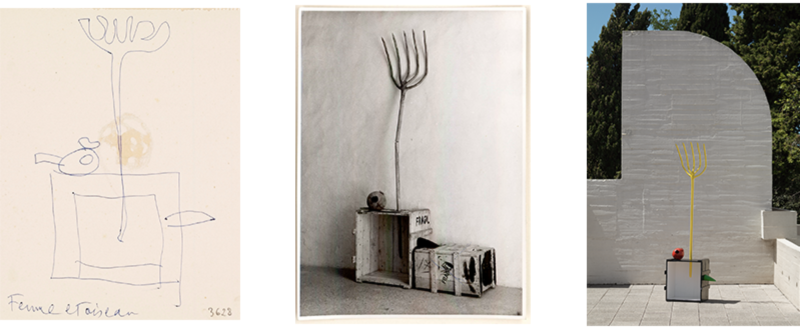

There are several types of these “papers,” as Cirici called them: sketches for paintings and drawings and sketches for sculptures. “The ones for paintings, aside from some that are still very figurative, reflect a variety of impulses. Sometimes there are several sketches for the same painting, which may be considered as steps in a process that could last for years. Through these drawings, we see how Miró’s language gradually gets pared down to the extent of eliminating any representation of the real world. In the sketches for sculptures, however, the point of departure is different. The objects he uses are what initially strike the artist. Here he starts off with reality, assembles the objects on the ground, and, before casting them, he draws them. You could say that above all they act as reminders.

There are also drawings produced as revisions of his past work, to which he returned at very specific moments in his career in order to approach the future. I believe having his entire collection of sketches at hand was very helpful to him.”

Preliminary drawing, assembled objects and sculpture Woman and bird, 1967. Fundació Joan Miró.

We ask if she sometimes wonders what direction to take from here. Whether working in an archive is a lonely task. Whether she feels the weight of responsibility. “We’re responsible for preserving the holdings that have been entrusted to us in the best possible conditions. It’s a task we take on jointly with conservators specializing in paper, but we’re also responsible for documenting and revising this material so we can make it available to everyone. And I wouldn’t say our work at the archive is lonely; quite the contrary. Those of us who work here have many opportunities to share information and knowledge with researchers. Contributing to research on Miró, either directly or indirectly, is one of the Fundació’s goals, and is also a source of satisfaction for us.”

A Commitment to Service

Archives are important for enabling the ongoing reinterpretation of a legacy – its different reception in each period, at each moment. Some aspects that might pass unnoticed for one generation may become relevant for the next. “Sometimes we have to shed light on certain information. To do so, we also have to build a proactive network with other archives, particularly with those that have Miró holdings; with universities, and with scholars. That is the future vision of the Fundació’s current director, Marko Daniel. To foster research, increase awareness of Miró’s work through the documents and drawings collection, and share knowledge.”

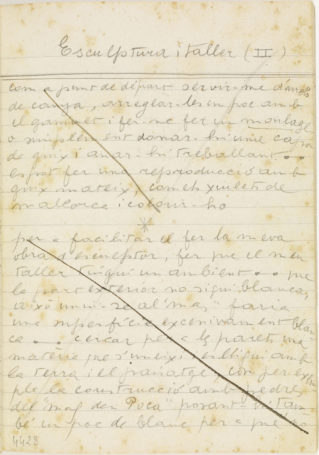

Notes. Sculpture and studio II. c 1943, Fundació Joan Miró

Were it not for this archive, we would know much less about Miró’s work process, about his thought, about his urge to synthesize everything to the limit, and about the methodical organization of his work in series. We would not know that the artist would go back upon the same piece time and time again over the years.

Safeguarding this collection reminds us of the meaning of Miró’s words: “An artist is someone who, as others remain silent, uses his voice to say something, and is obliged to have it not be useless, but rather something that can be of service to mankind.” And we at the Fundació are obliged to make this marvelous legacy available to the public in order to be of service to society.