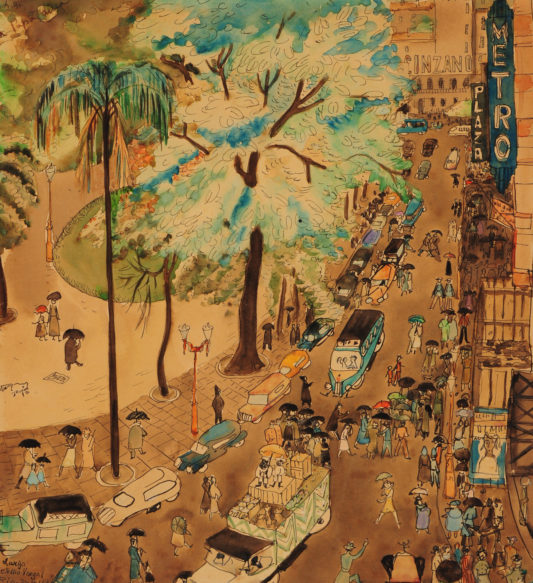

The architect Lina Bo Bardi, to whom the Fundació Joan Miró devoted an exhibition focused on her strong connection to drawing, conceived her projects as spaces that were accessible to everyone, brimming with nature and life. Her watercolours of urban scenes are also full of everyday life, like the piece illustrating the atmosphere at Praça Getúlio Vargas, in Río de Janeiro, in 1946. Amanda Bassa delves into this image and the ambient sounds surrounding the piece at exhibition to create a literary text that plays with the parallel worlds inside and outside the watercolour.

Praça Getulio Vargas

draNote: We recommend reading the text while listening to the audio track for the Lina Bo Bardi Drawing exhibition, courtesy of Fundación Phonos.

Night was falling and everything seemed full, heavy, a dog barked behind a man’s back. You could have sworn the snaking line of vehicles and the rushing pedestrians were crossing the room, making your reflection tremble in the glass. Actually, everything was happening on the other side.

It had gotten late. For everyone. At a time when the drivers were supposed to have been outside the city, walked into their homes, released their fingers from their briefcase handles, and patted their children’s heads, the car horns interrupted each other. It was a sensitive moment, when the crowds standing in line were supposed to have poured into the metro station, bought their tickets for the multiplex, located their seats in the stalls, first bell, the alarming extended rrrring of an old-fashioned device.

It could also be a Thursday evening. Soon the street lamps would be lit. Nobody had missed them, however: the shopwindow neons and the bright signs on the boulevard had been showing the passersby their way for quite a while. On this side, there was almost nobody left. You would have expected silence. Beyond the glass, the heat had become stifling and the voices were rising nonstop, because they could barely see the sky’s limit.

The moist wind was hinting at much more than the end of the afternoon.

The personified wind had this and other extraordinary, useful, and timely virtues, out there and inside many stories. That bothersome wind made the density of the branches in the park creak as if persuading one to whisper, and appeased the crown of the palm tree, which yielded and yielded. It nodded its head in stereotypies, agreeing with a question yet to be asked.

The sound of treetops growing.

The raised veins on the leaves.

Everything gained intensity, and, after a still moment, the downpour began.

From the pores in the pavement, dilated and shiny, rose a waft of tarry steam that made everyone drowsy. You saw it in the slow gaze of a woman led, arm in arm, by her companion. If she kept on going that way, she would end up disappearing. Your attention was drawn to her unwittingly: being so quiet, she became a strange hole in that landscape. You assumed that she wouldn’t disappear –she was there –, that she wasn’t an absence or a ripped-out patch. That she had withdrawn into her own pod, maybe to avoid getting wet. And that her shouts had been left inside her. You closed your eyelids and dreamed her dream in a different way.

Steeped in that hot rain, the people around her burst open like burning-hot corn kernels. At a critical point, from above, you could see them explode syncopatedly into half-spheres of protective colours. All the umbrellas popped as they opened, making the typical analgesic sound of mechanical devices. One had to seek cover: the rain was threatening to dissolve the traffic, the crowds of people and that entire liquid scene into a murky flood that would erase the avenue in one fell swoop, rush down the gutters and be released into the underground roar which, unknowingly, you walk upon.

Or it would clean the air. And that would be the end of that.

Among those walking across that square parenthesis of a street, nobody seemed willing to lose the position they had gained for just a few drops of rain. A group of pedestrians were talking cheerfully between the cars, above the hum of engines running in neutral. In that city, conversations prevailed over traffic lights. Some drivers, those who were used to it, joined in on the hullaballoo shouting comments from their car windows or announcing the latest news about their family, their job or some other chit-chat across the lanes. A truck loaded with fruit turned up the radio to party-mood decibels. With those ripe colours, the acid noise, and the entire procession of indolent vehicles behind it, it looked as though it were leading a carnival parade at the wrong time of the year.

On a corner, a man and a woman greeted each other from a distance, loudly, at a frenzied pace, bodies arching, arms outstretched, as if winding up to perform their best acrobatic swing-dance step. Their thrill made a shield of concentric waves, opening up a clearing on the street. And many families used the chaotic music of the evening to synchronize their rust-hued steps on their walk home. Even this late, there were still kids on the square: toddlers, children, and gangly teenagers; single, with siblings or twins, wearing capes, hats, and carrying parasols; solid, flying, wild. There were people everywhere, spilling over the sidewalks and their own outlines in a fluid mumble, forming colourful rows or happily equalized masses. You moved up closer to the glass, drawn to the deep, rhythmic vibration of a beat.

“La Fundació tancarà… La Fundación cerrará… The Fundació will be closing in five minutes.” After the announcement on the PA system, the museum guard cleared his throat and the ambient sound for the exhibition came to a stop. The other visitors emerged from the corners, while in an equally choreographed reverse motion, the paintings flattened out against the walls.

All the frienzied activity on the Praça Getúlio Vargas suddenly froze.

Its stories, brought to life by the magic spell of sounds, were summarized in the lasting instant that Lina Bo Bardi had captured in that drawing. For the first time, you noticed the wall label next to it: “Praça Getúlio Vargas, Rio de Janeiro, 1946. Watercolour and India ink on paper.” You knew it was time to leave when you became aware of the uncomfortable silence that had swallowed everything up.

At the ticket counter there was a traffic jam of tourists making a tremendous racket in six languages. Their voices were rising nonstop, because they could barely see the limit of the opening hours. Carnival at the wrong time of the year. In the hallway, the hullaballoo prevailed over clocks. Jobs, family, chitchat. Celebration. You slipped through politely, and before you knew it, you had made it outside with your things: bag, coat, scarf. Earphones. Night was falling and everything seemed dense, heavy. A group of insects buzzed behind you in six languages. You put your earphones on right then and there. A shield of concentric waves. You opened up a clearing. You withdrew into your pod. All of a sudden, everything was on the other side.

You reluctantly checked the cell phone messages you had silenced during that time –many, fairly important, almost definitive, and it was too late to do anything about them– and chose the soundtrack for disappearing. For heading down the hill in no rush, not yours or anyone else’s. To Believe. At least to begin with. Moses Sumney was trying to persuade you that you could still believe in something, but the music was telling you otherwise. The personified music had this and other extraordinary, useful and timely qualities in the center and the periphery of many stories. The Cinematic Orchestra picked at the strings of a guitar from another world over one of those legatos that shatter glasses and rip you up inside on a bad day. One of those times, usually a Thursday night, when, compared to the drawing of a square where you’d never been, reality turns as fragile as a line of pencil on a piece of paper.

And when everything that had been solid – the shapes of a building, the knots in an olive tree, the ID tag on a security guard or the plans for the rest of the evening, for life – is broken down into scattered marks.

It blurs, flattens, stops.

The feedback from the high violin notes brought on an unexpected tinnitus that made you wince in pain. When you were able to refocus your gaze, with the melody still piercing the bones in your skull, sewn into your eardrums, cramping the left side of your tongue, you saw that the evening light had shot a graphite shadow under your feet. You glanced at the dark blotch staining the terracotta floor tiles. You looked at it again and breathed in its wake of particles suspended in the air, its mineral texture, in your nostrils, at the back of your throat. You kept on staring until your eyes felt sandy and you were convinced that the impossible was true: that the shadow of your outline on the ground was made of a substance you could touch. You crouched down with your palms outstreched and planted your hand in it, making six furrows – a system of five satellites aligned over a moon in third quarter – and got it stained with ashes.

Strange holes in the landscape, rips in your stomach.

You closed your eyelids. Eyes slow. A sensitive moment. A critical point. A question yet to be asked. Chaotic music. The magic spell of sounds. Reverse motion. Unknowingly. First bell.

And your shouts were left inside you.

You stood up in a flurry and lifted a mess of black dust with your footstep, turned up the volume of the music without restraint and without regrets and without recourse, and started walking faster towards the exit.

In that icy corridor, with its vanishing lines and caricatures, you were the only thing moving.