Susana Carnicero graduated in Fine Arts and holds a post-graduate degree in Miró studies. Her fascination with colour as matter is the point of departure for a personal, subjective description in which a blue spot against a white background leads her on an exploration of the symbolism of this colour through a variety of artists.

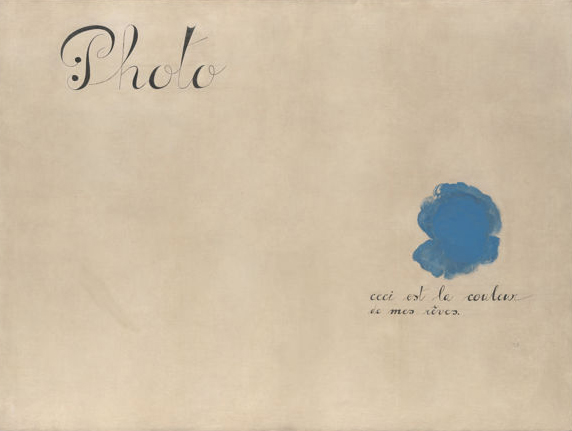

Ceci est la couleur de mes rêves

I love museum gift shops. Although it may sound uncool and seem a bit banal, I’m pretty much the typical museum visitor who walks out of an exhibition only to plunge into a consumer frenzy, buying pencils, notebooks, and postcards. This ritual, never admitted until now, culminates with the purchase of some useless but lovely object, which I carefully place within the little iconic landscape of my daily life when I get home. That’s how this story could begin.

Right after I graduated from university, I travelled abroad, and it was there, in a New York museum, where I made the priceless purchase of a postcard of a renowned work by Miró, Ceci est la couleur de mes rêves. At the time, this humble writer had little interest in Miró. I had no idea that the piece had been painted in 1925, when the artist was getting to know the surrealist group, and that the painting would mark a turning point in his career. But something caught my attention from the very first moment: that blue spot. That blotch that stained the surface of the painting like a mistake, and which, like an arrow, guided my gaze to the child-like handwriting that gave the work its title: Ceci est la couleur de mes rêves.

The colour blue could be considered a relevant visual element throughout the History of Art. Many artists have acknowledged the power of its hues, making it the inspiring vehicle of their most prominent works. Personally, looking back to the avant-garde, I would like to highlight Pablo Picasso’s blue period, in which his paintings were filled with cold tones aimed at conveying a melancholy mood. In Eastern Europe, the members of Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), led by Kandinsky, worked this colour into their paintings as a symbol of spirituality and eternity. In France, Matisse used the intensity of blue in his ‘wild’ paintings as an emotionally charged vehicle of expression. Yves Klein also comes to mind –captivated by this colour, he ended up patenting a brand of his own: International Klein Blue.

Chapel of Sant Joan d’Horta, 1917. Oil on cardboard. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona. Gift of Joan Prats © Successió Miró, 2018

In the case of our Catalan artist, his treatment of blue should not be considered from one single perspective: the Miró in Chapel of Sant Joan d’Horta (1917), who, faithful to the French post-Impressionists, bathes the sky in hues of violet blue, creating an interplay of contrasting cold and warm perceptions in the viewer, is not the same as the one appearing in the later Painting (1934), whose animated landscapes are darkened by the addition of the colour blue, heightening the dramatic quality of the pictorial scene.

Painting, 1934. Oil on canvas. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona. Gift of Joan Prats© Successió Miró, 2018

Nor is it the same colour formula which Miró applies to the piece mentioned above, Ceci est la couleur de mes rêves (1925). In this case, the artist appears to have cast off visual formalities (perspective, volume, contrasting light, etc.) to achieve his own dream-like world. And it is through calligraphy and a blue spot that he manages to weave together the realms of poetry and painting. This canvas, a forerunner of one of Miró’s pictorial periods, captures four of the key elements in the surrealist movement: photography, painting, dreams and automatism. Photography as an artistic category defended by the surrealists, indicative of progress and of the capacity to instantly capture reality; painting represented by the spot, which, located on the right of the composition and in a shade of blue that announces a series of later paintings, resembles a fluid surface of colour that allows the viewer to penetrate the layers of painting all the way down to the canvas. Last of all, dreams and automatic writing, the pillars of the doctrines underlying the movement led by André Breton. We could intuit that Ceci est le couleur de mes rêves paved the way for the dream-like paintings of 1925-27, usually with monochrome backgrounds of an “éter azuré” blue, as described by Isabelle Monod-Fontaine in her Note sur les fonds colorés de Miró[1], where the curator analyses the use of blues in the paint covering the artist’s canvases from that period and how the softness of the brushstrokes leads us to a more spiritual interpretation.

A good example of this would be Painting (The White Glove) (1925), whose monochrome blue background the artist achieved using a variety of technical resources –diluted layers, colour washes and loose brushstrokes – that reveal the direction of the gestures. They result in effects of translucence, transparency and refraction, all of which the historian Charles Palermo mentions in his essay Tactile Translucence (…)[2], evoking the notion of a timeless, dream-like space for the viewer.

Painting (The white glove), 1925. Oil on canvas. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona © Successió Miró, 2018

Many other works by Miró where blue is the protagonist come to mind, but my aim in this modest article is certainly not to overwhelm the reader with a visual analysis of a series of paintings; I would rather emphasize the chromatic vitality that Miró would identify as the colour of his dreams. In his conversations with Georges Raillard[3], the artist expresses the idea of daydreaming. For him, the creative moments of most intense activity and energy were the ones that led to his particular poetic universe. And those are the statements that make me reflect, bringing the thoughts of the Catalan master into my daily routine. Miró’s words stimulate me, insofar as they make me value my most immediate reality, and his burst of colour makes me appreciate, from the terraces of the Fundació Joan Miró – the place where I’m lucky enough to work – the blue sky and the colour range of a city that I love: Barcelona.

Translated by Deborah Bonner

[1] Isabel Monod-Fontaine: «Note sur les fonds colorés de Miró [1925-1927] ». Joan Miró 1917-1934, La Naissance du Monde. Ed. Centre Pompidou (Paris), 2004, p. 70.

[2] Charles Palermo: «Tactile Translucence: Miró, Leiris, Einstein». October Magazine, Ltd.and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Boston), 2001, p. 33.

[3] Miró. El color de mis sueños. Diálogos de Georges Raillard». Gedisa (Barcelona), 2018, p. 83.