Drawing on the philosophical tradition, Arnau Puig reflects on the concept of reality and the way Joan Miró transformed it through the lens of his own subjectivity. Mont-roig was the heart and the site of this almost mystical act by which reality was transformed into poetry.

Arnau Puig is an art critic specialising in sociology. He is a graduate in philosophy, founder of the artists’ group Dau al Set, and a regular contributor to several art publications. And an expert in the work of Joan Miró.

The Farm at Mont-Roig. Joan Miró’s Philosophy and Religion

Human beings draw ideas from the forms that our environment offers up, based on each person’s sensory and mental qualities, in the context of our affinities with the visions and feelings towards the surrounding culture. This perceptual aptitude and attitude is by no means a modern discovery; it can be found since antiquity. But we can express it in clear, simple, everyday terms by looking at what the empirical, sensualist philosopher George Berkeley thought in the eighteenth century.

There is such a thing as reality, the actual world that our senses perceive moment by moment. Focusing on sight, Berkeley said, when we are disengaged nothing exists. Concrete reality only exists when the senses are active, when we are alert and awake. And although we may think that this concrete reality disappears when we are not actively conscious, there is a “grand sensor” who is always awake, maintaining physical reality even when we are not active. This grand sensor is the Creator, creation itself. Berkeley, and later Miró, believed that the qualities of what we call reality (the world that each of us creates for ourselves, we would say now) reside in the spirit, and that their existence is thus realer and more objective than culture would have us think.

Joan Miró. Vegetable Garden with Donkey, 1918. Oil on canvas. Moderna Museet, Stockholm © Successió Miró, 2018

This was precisely Joan Miró’s attitude at Mont-roig del Camp. A highly sensitive man by nature, Miró saw that the cultural reality was not in tune with his essential, basic spirit. The social forms by which reality circulated lacked a personal, emotional dimension, they lacked intimate vision, elective affinities. When Miró looked around he did not see any of the things that he experienced or that he felt the need to possess, not just spiritually but also materially, physically. Like Berkeley, Miró wanted his beloved world, he wanted to draw it towards himself or else to fight it. Miró either gave himself over or pushed away. He was only interested in the vitality that splendid reality constantly offers up. What is more, Miró himself extracted the reality that he observed and made it real. Without his gaze, this world of other sensations, of sensibility, attachments, and fellowship would not exist. At Mont-roig, Miró became the “great sensor”. He was truly a creator of new reality for his own and others’ enjoyment. The artist, first a philosopher, questioned what was offered to him. He realised that each of us creates the world according to our feelings, desires, and plans. All that which has been called poetics. The reality that each person should be able to create from within.

Once found, this personal world (shareable at will – in his unique, personal way – with anybody who wants to identify or live with it) may be called religion or philosophy (life as a whole, integrating one’s own convictions and the considerations of one’s fellows). Thus, as Joan Miró saw and practised it, Mont-roig del Camp was the artist’s creative tangibility, the poetic geography created by the grand sensor. The entirety became a visual creation. Seeing it, one is persuaded.

Village and church of Mont-roig, 1919. Oil on canvas. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona. On loan from a private collection © Successió Miró, 2018

In short, we could say that culture is the the same as ideology and is determined by productive forces and relations of production (not in the determinism of the relationship, but in the ambivalence of the functional compensations), which establish what Francis Bacon called idola (or cultural perceptual determinants).

Even though sensations, sensibility, and emotions – in biophysiological terms (individual DNA) – are radically individual, they nonetheless act on the basis of the underlying idola. We are what we perceive, and our perception is determined by idiosyncrasy and ideology. As Berkeley (and Miró), would say, we pick up the sensations, the feelings and the emotions that we project. Reality (objectivity) is our own projection.

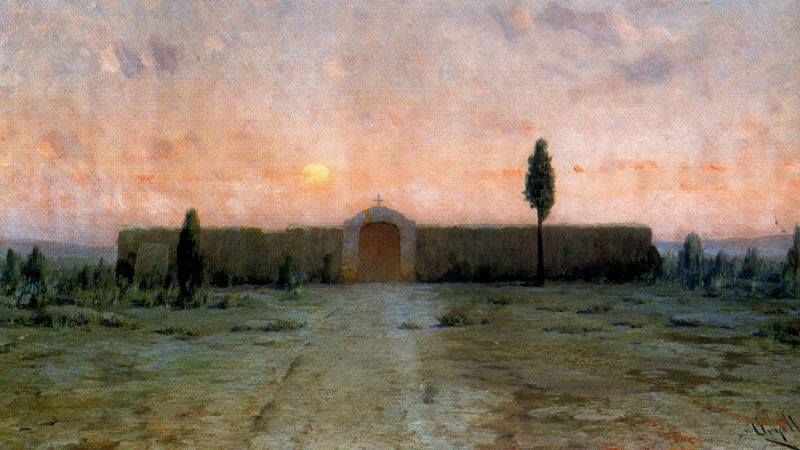

Modest Urgell (1839 – 1919). Cemetery. Colección Fons d’Art Caixa Sabadell

All of them looked at the same landscapes: Modest Urgell (any of the cemetery landscapes); Joaquim Mir, Vista de l’Aleixar (View of l’Aleixar, 1907-1913); Joan Miró, Mont-roig, església i poble (Mont-roig, Church and Village, 1919), Mont-roig, Sant Ramon (Mont-roig, Sant Ramon, 1916), La terra llaurada, (The Tilled Field, 1923-1924), Paisatge de Mont-roig (Landscape, Mont-roig, 1914) and Hort amb ase (Vegetable Garden with Donkey, 1918). They each offered up the landscape filtered through the lens of their own emotional-spiritual and social-perceptual qualities. Apparently, as Joan Miró still remembered into old age, his art teacher Modest Urgell once said to him, ‘listen boy, everything ultimately boils down to a horizon line, an above and a below. The horizon is the gaze; below is the harsh everyday reality; above is what you see of this reality.’

Joaquim Mir. Vista de l’Aleixar (View of l’Aleixar), 1907-1913

We can follow Miró’s process: first, reality as outline, then as the projection of one’s own affects and culture. And then the poetics (creation) through which each creates his own objectivity. The apse at Mont-roig is as important as the blades of grass that the donkey is grazing on. Each perceives the rugged geography of Siurana and projects it through the filter of his own conception of the world: tactile, sensual, sensitive, and social.