Joan Miró’s Mont-roig embodies his roots and his ties to the land and to the simplicity of everyday things. Mont-roig is a symbol and a reality, both personal and universal, and the point of departure for everything.

On the occasion of the opening of Mas Miró, the farmhouse where the artist spent many summers, historian and Fundació Mas Miró Director Elena Juncosa follows in the footsteps of the artist’s sensibility to place us in the unalterable timelessness of one of Miró’s most important emotional landscapes.

‘All I did was look.’ Mont-roig, the Landscape of Joan Miró

Mallorca, Barcelona, Mont-roig. Three essential places that configure a triangle from which Joan Miró’s art is born. Three settings in the artist’s life that now have their respective foundations, complementing and enriching one another with their differences. Barcelona, his birthplace; Mallorca, his refuge; and Mont-roig, a landscape – not only a visual landscape in the strictest sense, but also an emotional landscape which in turn is a source of inspiration and the origin of his creative strength.

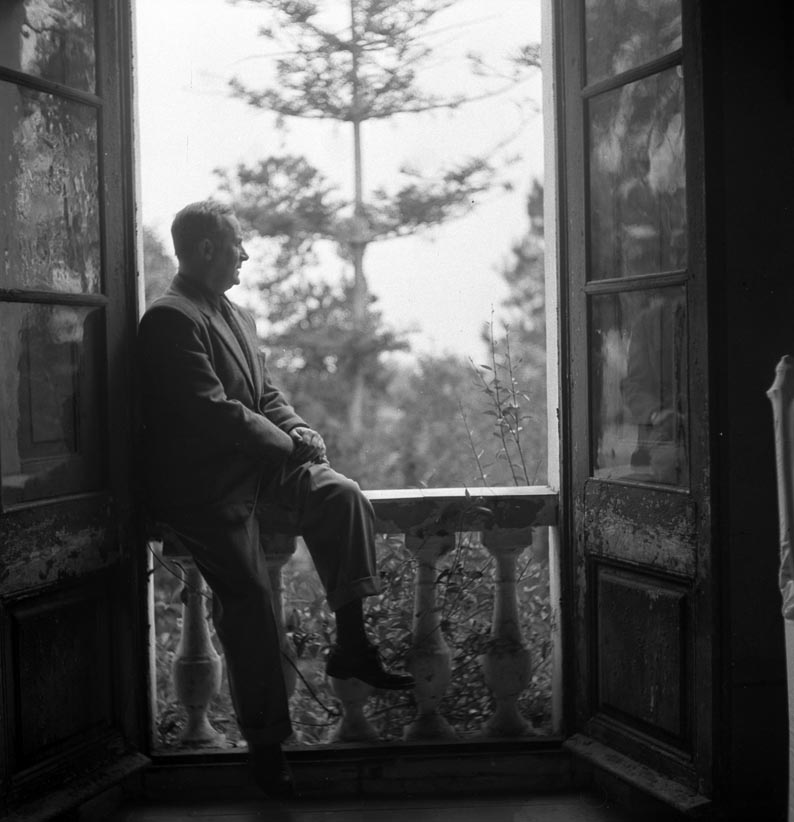

Joaquim Gomis: Joan Miró in Mas Miró, 1946-1950 © Hereus de Joaquim Gomis. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona

Miró always remained loyal to Mont-roig and to its well-known farm, to which he returned every summer as part of a mystical ritual. He was bound to it by a deep, vital, physical and emotional connection – one that led Miró to emerge as a paradigm of how one can be universal coming from a world as specific as that of Mont-roig. His strength arose from the close ties that bound him to this land – family ties, but also the ties of all the age-old folk traditions that Miró encountered there and which played a key role in the development of his work and his personality. The artist’s long trajectory has its point of departure in Mont-roig. Mas Miró is the place where, against his father’s wishes, Miró decided to devote himself fully to painting. And here, in direct contact with the land, he learned to work like a farmer, understanding that things come slowly through hard work and care.

Miró planted his feet firmly on the ground in Mont-roig. One of the first to identify the importance of this relationship was the critic Sebastià Gasch, who took note of Miró’s words and visited him at the farmhouse in October 1930: ‘Joan Miró once told us that to fully understand a painter, you had to visit him in his place of origin. […] Well, indeed, you have to go to Mont-roig – to that clear country, scrubbed clean, where the little grasses and leaves, the trees and the mountains are sharply outlined against an ever-blue sky, without atmosphere – to love the precise, penetrating, strong and intense painting of Joan Miró without reserve.’[i] And he describes the studio full of small, bizarre objects (the beginning of his assemblages), in that room on the second floor that he used before having a studio built next to the house, so that he could work on sculptures in the middle of the countryside in the late 1940s.

Joaquim Gomis: Miró Studio in Mas Miró, 1946-1950 © Hereus de Joaquim Gomis. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona

Miró’s complexity is simplified in Mont-roig. Mas Miró is an exceptional place because it attests to the course of the painter’s entire life and oeuvre. It is where he returned year after year, religiously, from 1911 to 1976, except for a brief hiatus during the Spanish Civil War. Walking through the farmhouse, you almost inadvertently embark on a journey through Joan Miró’s personal and creative trajectory. Mas Miró was the stage where some of the painter’s most important personal and artistic moments unfolded, such as the death of his father in 1926 and his first venture into sculpture a few years later. It has almost all remained just as the artist left it. This is of vital importance, because even during his lifetime Joan Miró expressed his concern about the future of Mas Miró, primarily when the first road was built very close by. Thinking of the future of his living spaces, Miró wrote: ‘Regarding the uncertainty of what the Mas Miró will become – the Son Abrines studio, the Son Boter studio with the shed next to it – I believe it is of the utmost importance to place it all in a way that not only emphasizes its human values, but also the objects and things that have had such a strong influence on my work. It would also be highly informative to have a section documenting these with large photographs of the landscapes and pieces of furniture in my everyday surroundings that served as stimuli for my work.’[ii]

Miró sank his feet into the soil at Mont-roig and compared his roots with the roots of the trees he looked out upon there: ‘In the soil of Mont-roig there are the roots of those two marvellous trees of that land: carob and olive. For me, the roots of the carob tree are like my feet, which sink into the ground, and that contact gives me enormous strength. I also admire that sign of vitality in carob trees, never shedding their leaves.’[iii]

His ties to the landscape of Mont-roig, first, and to that of Mallorca later on, had a decisive impact on his work and his language. Another Joan – Brossa – said that the landscape is a state of mind and time is an unfolding of history. We could see a similar unfolding in Miró, in his farm and studio in Mont-roig, in his home and studio in Palma. Family ties and the essence of the earth. Mont-roig, the land. Mallorca, poetry and light.

Many of Miró’s paintings from that early period depict the landscapes of Mont-roig. Visitors to the Fundació Joan Miró can see some of these pieces in the permanent collection rooms. Landscape, Mont-roig (1914) is one of the artist’s first known works and his first documented landscape, capturing the jagged outline of the mountains that impressed him so. Another painting, Village and church of Mont-roig (1919) is a view of the village from the first bridge, where if one now goes to the exact place where it was drawn, one discovers that almost a hundred years later, it remains practically the same. There is also Mont-roig, the beach (1916), the place the painter would reach walking down the Pixerota gulley, picking up the objects and natural elements that inspired him along the way.

Village and church of Mont-roig, 1919. Oil on canvas. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona © Successió Miró, 2018

Landscape, Mont-roig, 1914. Oil on cardboard. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona. On loan from the Gallery K. AG © Successió Miró, 2018

Miró’s landscape remains timeless and unalterable. Almost nothing has changed. The trees and farmlands appear to want to imitate Miró’s paintings, where he captures his love for this land and its silence. That silence is only broken by the highway that disfigures part of the landscape near a farmhouse that has been saved in extremis, doomed by progress. The construction of three different infrastructures led to an intolerable encroachment on the most intimate and essential of the spaces that Joan Miró left behind. Mas Miró is not only the painter’s farmhouse and studio; it is also its immediate surroundings, an atmosphere and a landscape, surrounded by ten hectares of land that are now, once again, being tilled. Miró’s world lives on at the farm. In the shade of the eucalyptus trees, in the silence of its rooms, in the expression of the graffiti and the blotches of paint on the floor of the studio, in the tilled soil surrounding the house that is now beginning to germinate, in the colour of the mountains – and, above all, in the blue of the sky that outlines the façade of the house on clear days, imitating the painting that made it famous. And you can still stroll through the carob groves, head down towards the Pixerota beach or climb up to the Roca and gaze out at San Ramon in perfect balance, just as Miró saw and captured it. And this makes it so, nevertheless, we can still imagine Miró’s daily life, absorbed in the contemplation of nature, of a small insect, of the sunset from the farmhouse tower, the sounds of country life, the silence of the night.

Sanctuary of La Roca and Sant Ramon © Joaquim Corts

Miró’s concerned question about the future of the farmhouse has finally been answered. The Fundació Mas Miró aims to capture his spirit and adopt his ties to the land with a modern approach. Accordingly, the project to recover Mas Miró has not focused solely on renovating the house and the studio, but rather on integrating both the land surrounding it and the landscape that inspired the artist into the overall narrative. You have to listen to the call of the earth and bind yourself to it, said Miró. With this aim in mind, the project has started up with a spirit of social responsibility and an emphasis on sustainability that began with the recovery of the arable land with organic farming, as well as a new conception of the itinerary through these different points as a continuation of the visit and a reflection about Miró’s relationship to Mont-roig.

The landscape of Mas Miró today © courtesy of the author and Fundació Más Miró, 2018

This month of April, part of Mas Miró will open to the public: a point of departure, the seed of a project that takes root in the landscape of Mont-roig and from whose sap new life will grow for the farmhouse. The origin of Miró’s inspiration and creation will be placed within everyone’s reach, allowing all to understand and experience the intangible values that Miró wished to convey. Ultimately, it is within human attitudes that all works of art have their roots.[iv]

All I Did Was Look (Joan Perucho in Roses, diables i somriures)

The gentleman smiles by the water’s surface between the mysterious shade of the eucalyptus trees and the crickets singing at dusk, while the farmhouse, like a ship, sails off slowly into the night; into the wandering, nocturnal memory of the dead.

Translated by Deborah Bonner

[i] Gasch, Sebastià. ‘Joan Miró a Mont-roig’, Mirador, Barcelona (8 October 1931).

[ii] Letter from Joan Miró to Josep Lluís Sert, Mont-roig, 1 October 1968.

[iii] As stated by Miró in the documentary D’un roig encès: Miró i Mont-roig (1979).

[iv] UNIVERSITAT DE BARCELONA. Acte inaugural del curs 1979-1980: Joan Miró, Frederic Mompou, Pierre Vilar, Doctors Honoris Causa. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona, 2 October.