To speak of architecture is to speak of spaces and volumes, of building components and of light. But how can you draw light? Those are the questions that Cristina Masanés raises in this article which – without intending to unveil the metaphor – tells us about an intimate and poetic walk through the geometries of the Fundació Joan Miró and other buildings designed by the architect Josep Lluís Sert.

Cristina Masanés, who studied philosophy, has written for a variety of media and art centres. She works as a freelance journalist, documentalist and exhibition curator.

‘Che bella voce.’ Architecture, Voice and Speech

The Slovene philosopher Mladen Dolar begins his book A Voice and Nothing More with a story. In the middle of a battle, the commander of an Italian company gives an order to his soldiers in the trenches. ‘Attack!’ he shouts in a loud, clear voice. But none of them move. He gives the order a second time, to the same effect. The third time, which elicits no movement among the troops either, he hears a faint voice peep out of the trench saying, ‘Che bella voce.’ The voice – or, in this case, the beauty of a voice – has superseded an order, eclipsing it to the point of rendering it non-existent. And the fact is that one thing is a voice – physical, personal and unique – and a very different one is speech – or the universal and shared web of language.

Creative Commons

I am indebted to Josep Lluís Sert for a truly moving initiatory experience. For those of us who were children during the late years of Franco’s dictatorship, family visits to the Fundació Joan Miró building in Barcelona are reminiscent of moments of discovery, of wonderful encounters with something that we couldn’t quite pin down at the time but that years later we learned to recognize as a first experience of architecture or, to be more specific, of architecture as voice. The memory of that white building with an unpredictable itinerary, literally pierced by light and covered with large patches of blue sky, was associated with a new emotion, something entirely different from anything I had experienced before then.

Without any desire to undermine the magic of the spell – nor would I be capable of doing so – over the years I have tried to pinpoint some of its elements, like the itinerary the architecture suggested: instead of presenting the building as a single block, it broke it down into small bodies or volumes distributed throughout the site and set around a wide-open square courtyard. This flow tied into some of the childhood stories that invalidated the logic of a single direction. ‘I’m late,’ said the white rabbit to Alice, who was willing to break all the customary rules for travel. In addition to the itinerary, the skin of the building was also different. This museum was impossible to draw: it had been painted with white and light. How can you draw light? But among all the surprises we encountered, the roof, which we could walk on and had no tiles, was an unparalleled invitation to follow Alice’s rabbit through the looking-glass. Out there, under the sky, we were overcome by an acute sense of sinuosity and movement, like a wave, that has resisted the passage of time.

John Tenniel, illustration for Alice in Wonderland, by Lewis Carroll. First edition, 1865.

I have tried to track down Sert’s drawings for the Miró building in Barcelona. Those drawings inevitably send us back to a previous path, an approach to construction that the architect had already applied to two other buildings which, curiously, were also associated with art and with the close friendship Sert shared with Joan Miró. The first is the painter’s studio designed by Sert in 1953 as a building adjacent to Miró’s home at Son Abrines in Palma de Mallorca. The second is the project that the architect began designing in 1958 for the art dealers Marguerite and Aimé Maeght: the building to house the couple’s foundation in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, a small medieval village in the Alpes Maritimes. These two friends and dealers of Miró’s work – who also represented Calder, Giacometti, Matisse and Chagall, among others – had listened to the artist when he suggested that they contact Sert for their contemporary art space. By then, Sert was entirely American – he had been granted U.S. citizenship and been appointed Dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Design – and eager to re-examine his roots, attempting to fit the clean and functional modular rationalism of northern architecture into the white organicism of the Mediterranean tradition.

The same sinuous gesture is present in the roofs of all Sert’s buildings related to Miró; it’s a gesture that provides movement and is often associated with the effort to capture light. While in the painter’s studio two Catalan quarter-vaults meet at their lower vertex, at the Fondation Maeght two half-vaults are set upside-down in relation to their usual position, forming two half-circumferences which, like two impluvia, look up to the sky. A functional element like an impluvium, so necessary in a climate like that of the Mediterranean, where rainwater must be collected and distributed, breaks the horizontality of the roof and lightens up the architectural mass.

Sert Studio, Miró Mallorca Fundació, Palma de Mallorca

Fondation Maeght, Saint-Paul-de-Vence

Construction of the roof for the Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona. Joaquim Gomis, c. 1974 © Hereus de Joaquim Gomis. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona

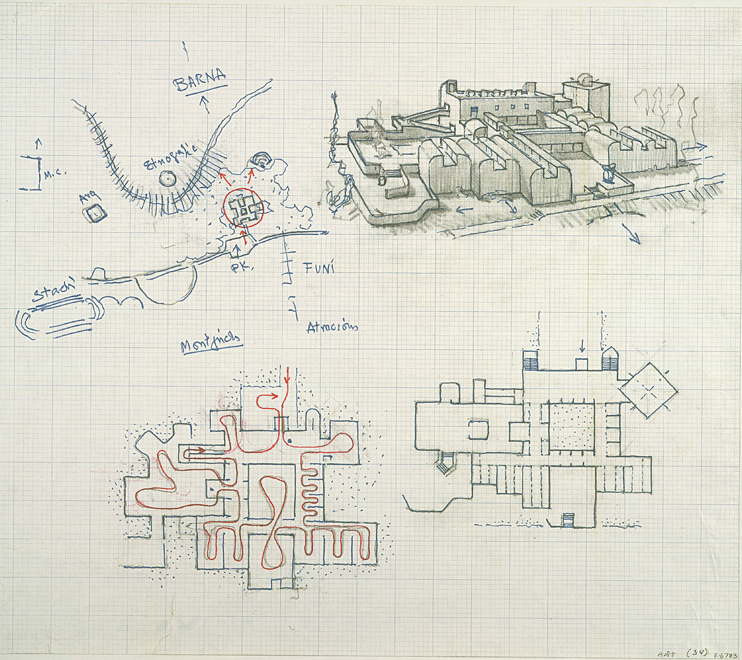

Sketches for the Fundació Joan Miró: location, circulation plan, floor plan and overall perspective, Josep Lluís Sert. Courtesy of the Frances Loeb Library. Harvard University Graduate School of Design

But the most thoroughly developed solution is the one for the Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona: a quarter-vault placed horizontally on the roof, repeated time and time again like a wave. Here, the Catalan vault, so simple and effective, becomes an element for experimentation, a case study in which different formats and solutions are applied. Concrete is a good ally: its ductility turns the structural solutions into visual statements. While the concrete delineates a quarter-vault or a quarter-cylinder, the vertical surface that closes the vault is replaced with glass, turning the vault into a skylight. Although from the outside the effect is that of a wave, from the inside the light doesn’t pour in from the top down, but sideways, bouncing off the white interior of the quarter-vault and spreading almost atmospherically into all the corners of the space. Although the sunlight effect is undeniable, the source or the entry of light generates a climate of mystery. The schematic geometry of the roofs in Miró’s studio and the Fondation Maeght, which clearly identify these two buildings, have led to an elaborate system that combines a heightened sense of sinuosity with a calculated treatment of light. In the Barcelona building, the architect carries us through the looking glass. ‘Che bella voce,’ said one the soldiers in the trenches, timidly, about the Italian commander.

Just as there is something that transcends language and ventures beyond it, buildings also have the ability to expand towards the realm of meaning, and then we speak of architecture or of voice. In March 1951, at a symposium held in New York, Sert stated: ‘Architecture today has to be more functional and cannot exist without a sense of artistic values. Without them, we would produce buildings, but not architecture.’

Documentary J.L. Sert, A Nomadic Dream, Pablo Bujosa Rodríguez, 2013, 72’. Produced in Spain and the United States

Translated by Deborah Bonner