‘Miró is said to have spent his afternoons and evenings reading poetry and listening to music; his nights, taking it all in and dreaming; and his mornings, bathed in bright light and total silence, working on his paintings. Every brushstroke, a note shattering the white sky.’

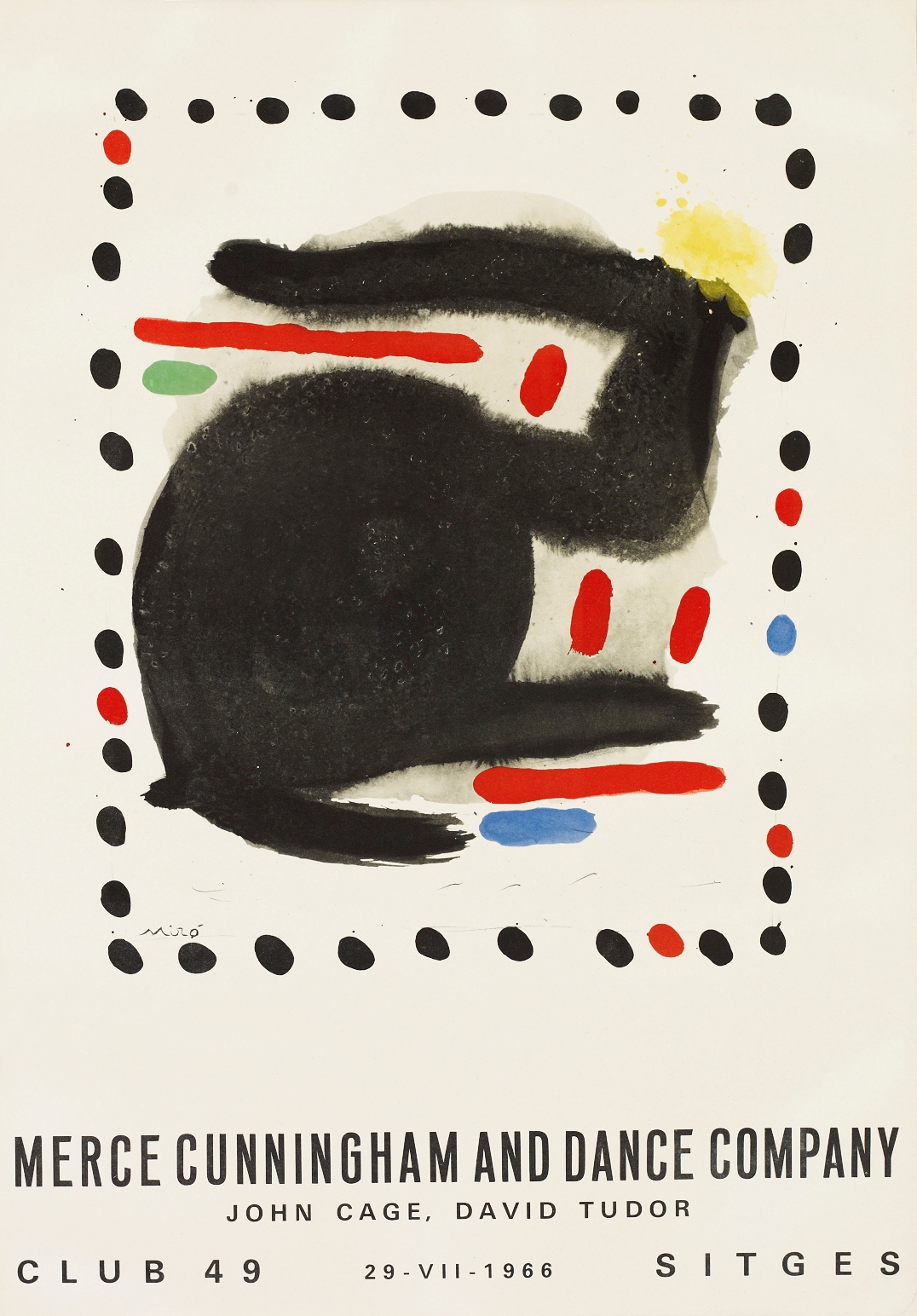

Coinciding with the recent publication of Joan Punyet Miró’s book Miró & Music (Ed. Alrevés, 2017), poet and cultural agitator Eduard Escoffet explores the close connection that Joan Miró developed with music and his ‘likeminded spirits’ in other creative fields. In a sentimental journey that begins with Miró’s poster for John Cage and Merce Cunningham’s legendary performance in Sitges in 1966, and travels all the way to the Nits de Música at the Fundació, Escoffet brings us closer to the artist’s legacy, ‘an attitude, a spirit of openness and an urge to engage in dialogue with the present.’

Miró as a Sounding Board

A few years ago, browsing in El Astillero bookshop, my eye was caught by an unfamiliar poster that touched on several of my passions: in July 1966, Club 49 brought the Merce Cunningham Dance Company to perform in Sitges alongside John Cage and David Tudor; Miró designed the poster. The very poster that now hangs in my dining room. More recently, in December 2016, when I went to the exhibition Escuchar con los ojos. Arte sonoro en España, 1961-2016 [Listening through Your Eyes: Sound Art in Spain, 1961–2016], at the Fundación March in Madrid, I discovered the letters that had sparked this partnership. On 25 November 1965, Jacques Dupin wrote to John Cage from the Maeght Gallery in Paris to tell him how delighted Miró was that their forthcoming tour would include Spain. He also confirmed that the artist was willing to create a piece to promote the performances in Barcelona and Saint-Paul-de-Vence for them to use in any way they saw fit. Some days later, on 3 December 1965, John Cage replied: ‘Miró’s gift of a painting makes our plans to come to Europe next summer and fall absolutely feasible.’ At that time, Miró was a renowned artist with considerable commercial cachet, whereas Cage and Cunningham, although respected in influential circles, had neither the economic resources of artists like Miró nor anything like the same level of popular recognition. In fact, keen to work with them in whatever way he could, it had been Miró’s idea to bring Cunningham and Cage to Catalonia; and it was his gift that made the tour a real possibility. Now, more than fifty years later, as well as attesting to a heart-warming friendship, this poster also reveals Miró’s knack of seeking out likeminded spirits in other areas and other contexts (and then bringing them to Catalonia). And for me personally, it links three worlds that have shaped who I am: Miró, Cage and Cunningham.

Programme of ‘Merce Cunningham and Dance Company’ performance, 1966. Printed paper. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona © Successió Miró, 2018

Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Francis Miroglio and Joan Miró at the Nuits de la Fondation Maeght, Saint-Paul-de-Vence, 1966. Photo: Archives Fondation Maeght, Saint-Paul-de-Vence (France)

The Fundació Joan Miró has also explored this link between art and music. Because the Fundació’s mission isn’t simply to conserve a series of artworks, Miró’s heritage, but also to keep alive a legacy: an attitude, a spirit of openness and an urge to engage in dialogue with the present. For many years it ran a series of events called Nits de Música. Together with the Setmana de Música Experimental at Metrònom (under the baton of the exceptional Barbara Held) and G’s Club at Sidecar, these music nights taught me much of what has shaped my tastes in music. At that time, it was rare to see experimental musicians from the international scene. But for a few short days, many of us suddenly felt we were living in a normal city, able to blur boundaries and explore poetry, music and visual arts as a creative continuum. Experimentation, improvisation, jazz, electronic music, sound art… On those evenings at the Fundació, I was privileged to see musicians who had a huge impact on me, including the likes of Agustí Fernández, Evan Parker, David Moss, Phil Minton, Hans-Joachim Roedelius, Embryo, Joan Saura, Cluster, Lê Quan Ninh, Carles Santos, Derek Bailey, Zeena Parkins, Chris Cutler, Macromassa, Iva Bittová, Hiroshi Kobayashi, Nuno Rebelo, Ràeo, Susie Ibarra, Josep Maria Balanyà, Fred Frith, Il Gran Teatro Amaro, Tim Hodgkinson, Xavier Maristany, Peter Brötzmann, Alfonso Vilallonga, Lol Coxhil, DJ Zero and Pascal Comelade, to name but a few. And one of the few concerts from those nights I have managed to track down on the internet features Pascal Comelade at a performance he gave there in 1995 accompanied by some of his legendary musical partners in crime from Barcelona: Gat, Mark Cunningham and Jakob Draminsky Højmark. You can watch it on Summa, the Habitual Video Team’s online archive. I think Joan Miró would have loved Comelade and his troupe’s version of ‘Cant dels ocells’. As at all the concerts I went to, the auditorium at the Fundació was filled with a very special atmosphere: a fleeting celebration that has left few traces in the city yet left its mark on everyone who was there. This is the essential value of music that I have always strived to conserve in my own creative work: its ephemeral nature.

Pascal Comelade concert with Gat, Mark Cunningham and Jakob Draminski Højmark as part of the Nits de Música series. 27 July 1995. Photo: Pere Pratdesaba. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona

Embryo concert as part of the Nits de Música series. 2 September 1999. Photo: Pere Pratdesaba. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona

Miró is said to have spent his afternoons and evenings reading poetry and listening to music; his nights, taking it all in and dreaming; and his mornings, bathed in bright light and total silence, working on his paintings. Every brushstroke, a note shattering the white sky. I like to think it was his way of dancing. A very different dance to Pollock, who reacted spontaneously to the jazz he listened to at full blast: Miró’s would be a more cerebral, unhurried dance led by silent, white serenity. A few years ago, Tres, artist of silence and a good friend of mine, curated a season at Espai 13 under the heading Explicit Silence (2009–2010), followed by a second season entitled Implicit Sound (2010–2011). I have always liked to imagine a conversation between these two artists—in fact, not just a conversation but a blackout concert at the Fundació like the ones Tres used to give, only this time with Joan Miró as the sole spectator, with all the silence in the world to dance to. When I dance, I like to lose myself in Miró’s landscapes and constellations, grabbing hold of a point like a note by Steve Reich.

Slow (Agustí Fernández, David Mengual, David Xirgu i Dani Domínguez) concert as part of the Nits de Música series. 28 July 2005. Photo: Pere Pratdesaba. Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona

At the end of his life, Miró began burning his increasingly empty canvases—just like Jimi Hendrix did with his guitar. He even trampled them underfoot: the sounding board that hangs from the ceiling of the auditorium, painted a month before the Fundació opened, in 1975, bears the marks of his footprints. To create it, a chipboard panel was laid on the ground and, after only a couple of days of hard work, the artist proceeded to walk over it, as if crossing a field, drawn by a distant sound. Seen from a distance, out of the corner of my eye, it has always looked like a rocking chair, in the same way that the 1966 Sitges poster has always concealed a rabbit. As if my thoughts were seeking sanctuary in the farmhouse at Mont-roig del Camp.

Translated by la correccional (serveis textuals)