From Le Corbusier’s sketches for a monumental ziggurat-museum in Geneva (Mundaneum, 1929) to urban development plans for cities like New York in the 1920s, Mesopotamian forms have had a profound impact on modern visual and architectural culture in the West.

As part of the Sumer and the Modern Paradigm exhibition, the archaeologist and researcher Maria Gabriella Micale explores how twentieth-century architecture was influenced by the drawings of the pioneers of archaeology, reinterpreting and recasting the architecture of the ancient Near East in the design of modern buildings.

The Fate of Mesopotamian Architecture in the Spiral of Image Reproduction

In the region corresponding to modern Iraq, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the archaeological exploration of the ancient Near East began. Before these missions conducted by the pioneers of Near Eastern archaeology on behalf of European museums, no significant architectural remains from ancient Assyria and Babylonia were known. In fact, their history was only partially known and that knowledge came via biblical and classical textual sources (i.e. Herodotus), whose famous descriptions often served as the foundation for the fantastic images of famous Mesopotamian lost cities created by European artists well before their actual discovery (Fig. 1). Thus, in theory, the material discovery of ancient Mesopotamia should have bridged the gap between imagination and reality, at least concerning these artists’ architectural culture. However, a closer examination of the question reveals that this logical expectation has not been fulfilled, and that the image of ancient Near Eastern architecture was not reconstructed on the basis of archaeological research even in some allegedly scientific publications.

Fig. 1. Pieter Brueghel the Elder, The Tower of Babel, 1563. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The Sumer and the Modern Paradigm exhibition opens a discussion about concepts such as artistic reception and cultural memory. However, the power of architectural images to embody different cultural meanings through similar formal features is often underestimated. In the light of this, it is important to emphasize that the connection between Mesopotamian architecture and modernity was mediated by the drawings presented in the first publications of Assyrian discoveries (Fig. 2). These architectural (re-)constructions, designed as an integral part of the archaeological publications, had an impact not only on the history of the scientific interpretation of ancient architecture, but also on the construction of modern architectural designs and occasionally on the reconstruction of real or alleged traditions (Fig. 3). However, the importance of these drawings reconstructing ancient Mesopotamian architecture lies also in the fact that they clearly functioned as vehicles for ancient architecture to enter into modern design, thus creating a powerful spiral of images traveling through time.

Fig. 2. Victor Place – Félix Thomas, Palais. Ensemble de la porte Z. du harem, Ninive et l’Assyrie, 1867-1870. Source: General Research Division, The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Fig 3. Chaldean Church, Aleppo, Syria, 2007. Photo: Maria Gabriella Micale.

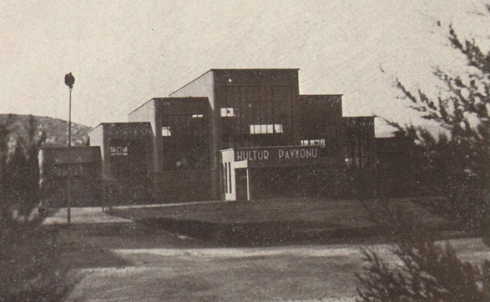

Le Corbusier’s sketches for the Mundaneum in Geneva (1929) exhibited in Sumer and the Modern Paradigm are a typical example of the use of Mesopotamian forms in modern Western visual and architectural culture. A number of more or less contemporary (and more or less famous) projects show how widespread the Mesopotamian temple-tower/ziggurat forms were in modern building design, regardless of the artistic movement to which their authors belonged (Fig. 4). It is difficult to detect the assumption of the single choices of these formal volumetric expressions. Hugh Ferriss writes about the American urban planning regulations in those years: ‘The building rises vertically on its lot lines only so far as is allowed by law […]. Above this it slopes inward at specified angles […]. A tower rises, as is permitted, to unlimited height, being in area not over the fourth the area of the property […]. The mass thus delineated is not an architect’s design: it is simply a form which results from legal specifications.’ And further: ‘The ancient Assyrian ziggurat is an excellent embodiment of the modern New York legal restriction: may we not for a moment imagine an array of modern ziggurats, providing restaurants and theatres on their ascending levels?’ (from The Metropolis of Tomorrow, 1929: pp. 74, 99). An explicit correspondence between the ancient religious function of a ziggurat and modern monumental buildings evoking an ancient tower is not apparent (the project for a Soldiers’ Memorial Church by Boehm, Goettingen, 1923 [Fig. 5] is an exception in the context of a religious architecture dominated by classical models). On the other hand, a clear reference to Mesopotamian culture can be seen in some monumental projects from modern Turkey dated between the 1930s and 40s that could be interpreted as an endorsement of modernism (Fig. 6). Even though no Mesopotamian tradition could be claimed, the reference to the ziggurat may have been connected to the idea of a racial/linguistic relationship between Turks and ancient Sumerians supported by some intellectuals in the 1920s. In these examples, architecture enters the public space and creates visual links that aim at public recognition of formal features and meanings from Mesopotamia – whether these links are based on substantial cultural ties or not.

Fig. 4. Sigismund Vladislavovich Dombrovski, Meeting Place of the Peoples, 1919. Courtesy: Wolfgang Pehnt.

Fig. 5. Dominikus Böhm, Soldiers’ Memorial Church, Goettingen, 1923. Courtesy: Wolfgang Pehnt.

Fig. 6. Bruno Taut, the 1938 Izmir International Fair. The Ministry of Education’s “Culture Pavilion”. Source: Arkitekt 1939/9-10: 202.

Fig. 6. Bruno Taut, the 1938 Izmir International Fair. The Ministry of Education’s “Culture Pavilion”. Source: Arkitekt 1939/9-10: 202.

Was the fragmentary materiality of Mesopotamian architecture brought to light by archaeology the source of the tower-shaped projects in both Europe and Turkey? Or were perhaps the archaeological drawings published in the scientific literature to explain and support the different hypotheses of reconstruction, the inspiration for these buildings? In either case, the image is perceived and used as if it were the reality, while the architectural forms that this image conveys have the power to embody different meanings in different contexts.

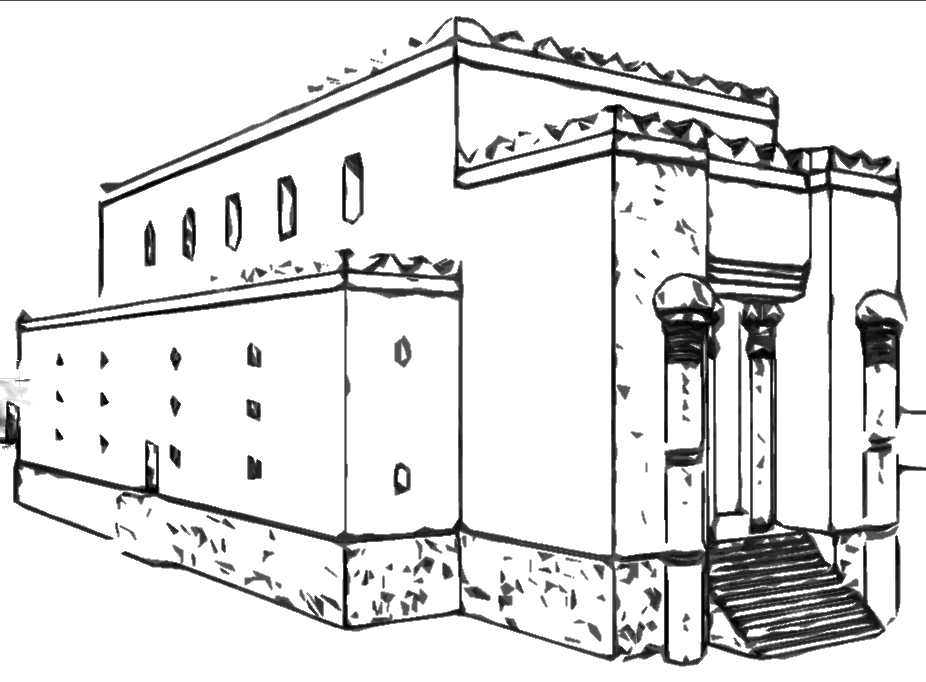

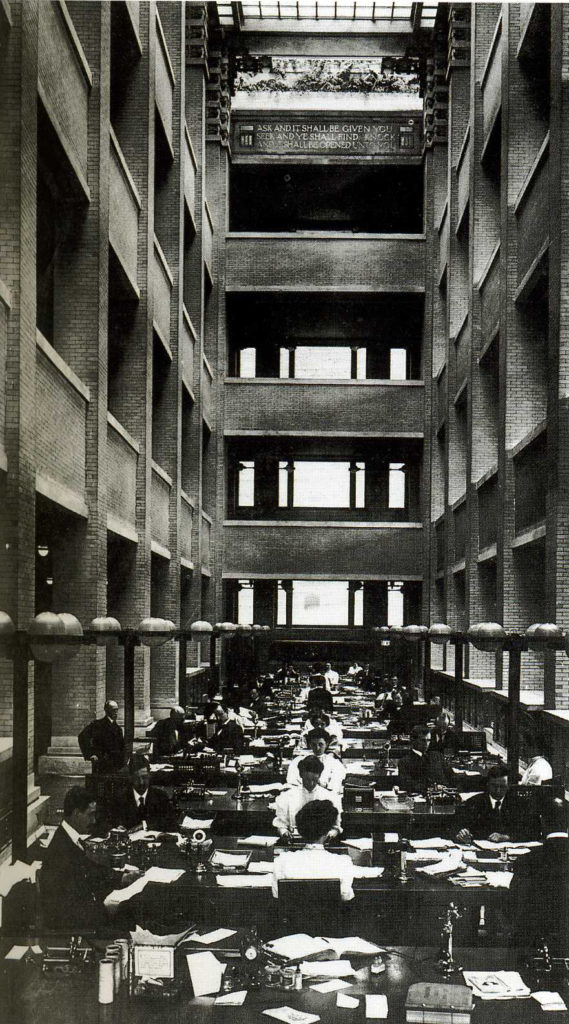

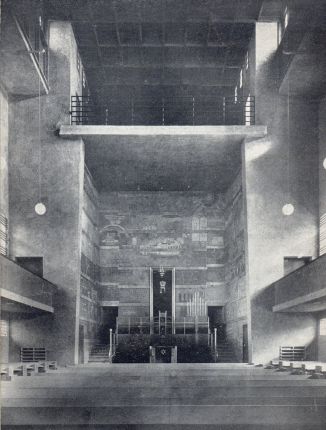

However, how much of modern and contemporary architecture draws on these archaeological drawings? And how much within these drawings actually derives from the individual visual culture or educational background of the archaeologists reconstructing ancient architecture? The majority of Robert Koldewey’s drawings seem to suggest his tacit compliance with the principles of the Rational School, while Walter Andrae, as a student of Cornelius Gurlitt at the University of Dresden, appears to have been influenced by the principles of the German Jugendstil and the compositional perspectives in vogue with the Gothic Revival in the 1920s. Architectural reconstructions of ancient Near Eastern architecture and urban contexts were heavily influenced by projects that were supposedly well known at the time when those reconstructions were made. Examples include the perspective reconstruction of the Citadel of Khorsabad (c. 1938), which recalls both the National Mall and Memorial Parks in Washington, D.C., conceived by the McMillan Commission (1901), and the Plan for a City of Three Million People by Le Corbusier (1922). A much more recent archaeological reconstruction inspired by a modern building may also be the perspective drawing of the Temple of Salomon by Theodor Busink (1970) (Fig. 7), whose model may have been the famous Larkin Administration building designed by Frank Lloyd Wright (1906) (Fig. 8). Interestingly, the interiors of Wright’s building (Fig. 9) seem to have also inspired the interiors of the Synagogue of Plauen designed by Fritz Landauer, destroyed during the Kristallnacht (9-10 November 1938) (Fig. 10) – a parallel which, however, may only suggest that Wright’s famous building served as a model for a wide range of modern designs as well as modern reconstructions of ancient buildings, albeit as a shape disconnected from meaning and function.

Fig. 7. The Temple of Salomon according to the idea of Th. Busink, c. 1970. Graphic editing after Busink’s reconstruction: Maria Gabriella Micale.

Fig. 8. Frank Lloyd Wright, Larkin Administration Building, Buffalo, N.Y., 1906. Source: Wikiarquitectura.

Fig. 9. Frank Lloyd Wright, Larkin Administration Building, interiors. Source: Wikiarquitectura.

At the end of this short overview one can say that unlike figurative art, which establishes a direct relationship between ancient and modern artists, ancient Mesopotamian architecture reaches the modern world only via the mediation of the recomposition and interpretation of its fragments by archaeologists and architects. This mediation is, however, bi-directional, since modern concepts of space and volume deeply impact the archaeologist’s way of interpreting and communicating ancient architecture. It is this binary relationship between ancient and modern that is the real key to understanding the creation of a repertoire of prêt-à-porter images of ancient Near Eastern architecture – images increasingly divorced from their artistic, cultural and archaeological contexts – that have the power to ‘orientalise’ architecture as needed in both East and West.

Fig. 10. Fritz Landauer, synagogue, Plauen, interiors, 1930. Courtesy: Architekturmuseum Schwaben.

Edited by: Deborah Bonner

very nice collection .thanks for sharing…